Israelis putting their bodies on the line

JVL Introduction

This long report is an in-depth study of a handful of Israelis who are among those committed to supporting the Palestinian shepherd communities in the South Hebron Hills.

They, as we have reported often, are under increasing pressure to evacuate their lands as settlers, aided and abetted by the army, harass them without warning.

What is fascinating is both the diversity of background of the Israelis who come out in support, and their steadfast commitment to what they are doing – doing their best to make an intolerable situation tolerable, at least for a little while longer.

The original article is accompanied by many wonderful photos – you can see them here.

RK

This article was originally published by Haaretz on Fri 2 Feb 2024. Read the original here.

Meet the Israelis who are trying to physically block the ethnic cleansing unfolding in the West Bank

Under the cover of war, backed by Israel’s army and police, settler violence targeting Palestinian shepherding communities is surging. These Israeli activists are putting themselves in harm’s way to protect them

About once a week, Netta Ben Porat leaves the yellow ribbon identified with the return-the-hostages movement at home. She spreads a keffiyeh on the dashboard of her car, hangs Muslim prayer beads from the front mirror. A Palestine flag is already hidden in the glove compartment. “I am here – and also here, right?” she says. With such trappings she feels safer driving on the roads of the West Bank with yellow Israeli plates, but only before she gets out of her car and goes into the field. “There the fear is of settlers, who truly have no limits. They already tried to kill me once.”

Sitting in a café near her home in Modi’in, in central Israel, there is nothing about Ben Porat that hints at her longtime experience in the territories. The manager of a team at a high-tech company and the mother of three, she gets genuinely enthusiastic when talking about bugs and code. “If you forget about my activism, I’m the most normal person in the world,” she insists.

Ben Porat’s path to activism started on Balfour Street in Jerusalem, across from the prime minister’s official residence. “At the time I was involved in what’s now known as the ‘Anyone but Bibi’ protest,” she explains. “I thought that it wasn’t the right time then to fight the occupation, that we needed to finish that struggle first. And then, in 2021, I joined a group of people who were escorting shepherds in the West Bank.” Two settlers on motorcycles showed up and drove through the flock to scare the sheep. “I was stunned, I simply couldn’t believe it. Today something like that is almost amusing – it’s nothing. But the evil simply shocked me. After a little while, I began to go there once a week.”

Most of the occasions when she accompanied Palestinian farmers and shepherds, to offer them support as they made their way to the fields, had been uneventful. “You hang out in the shade, listen to music, doze off a bit and go home. You see deer, foxes and birds, the lambs are bleating in the background. All in all it’s quite pleasant.”

But that was not the case one day in November 2021, when Ben Porat went to help olive harvesters in Surif, near the settlement of Bat Ayin, in the Etzion Bloc south of Jerusalem. “Their groves were neglected, because they were really frightened to go there,” she recalls. “For a few hours it was fun, we tended the trees and picked olives. We were eight Israelis, I was the only woman, along with some Palestinian families. The army was there to guard us, because it was all coordinated with them. A group of young settlers kept trying to approach us and the soldiers kept them at bay.

“Around noon, the soldiers disappeared. About 10 minutes later, we saw the settlers getting organized. Dozens of them showed up, coming from three directions. Kids with machetes and clubs. We saw a security vehicle from a nearby settlement bring in more young people, and the security chief himself was standing above, holding a shotgun. It was clear they were organizing for an attack. For 45 minutes we tried calling the army. We said: ‘We see them, please get here, get here!’

“It doesn’t matter how many stories I’d heard about settlers hitting people,” she continues, “I didn’t think they would hit me. But when I saw that a fistfight was about to break out, I moved to the side, away from the center of the melee. I thought I was protecting myself. And then two of them targeted me.”

Footage from that day shows dozens of masked people streaming down from the hills and hurling stones at the Palestinian harvesters and the Israeli activists. The two who homed in on Ben Porat began to throw stones at her, which landed ever closer, and then charged wildly at her. The video ends. They bashed her on the head and body with clubs. “I think the amount of blood that spurted out of me scared them a little, because they ran off,” she says. The doctor who later stitched her up at a clinic in Surif said that the gash in her head was small but very deep; a nail had probably been attached to the club. A short time after she was injured, she says she developed an autoimmune disease that may be related to that incident.

“The army knew at any given moment exactly what was happening, and chose to stop the goings-on the moment after we were beaten up,” she says. “As far as I know, none of the settlers was taken into custody except for one, and he wasn’t tried, because he struck a plea bargain. The police prosecutor termed it a ‘dispute between neighbors.'” A month later she was back accompanying Palestinians.

Ben Porat was born in Kfar Kisch, a community in northern Israel, and grew up on Kibbutz Kabri, not far from the Lebanon border. Most of her extended family is Orthodox or ultra-Orthodox; some were among the founders of Elkana in the West Bank. She often escorts shepherds in the shadow of settlements where her relatives live. She met her husband of over 20 years when he was still a Likud supporter.

She makes no secret of her views or activities either at home or at work. There were times when she would show up at the office after having been beaten, as if taking part in the Judea-Samaria version of “Fight Club.” She testified about the Surif incident before the United Nations Commission on Human Rights last March. She was given the option of testifying behind closed doors, but rejected it out of hand. “A significant part of what I do is my testimony – the fact that I talk about it,” she notes.

What do your children know about what you do?

“They know that police officers hit me, they know that Mom was beaten by settlers. They know that I stand by the Palestinians. They know, and they feel the ‘ricochets’ from what I do, in their social lives.”

What keeps you going back after all the attacks?

Do you feel that your activity is bringing about change?

“A change in the fact that we are destroying communities and a culture? No. Sometimes it delays things a little, sometimes it makes the Palestinians feel a little more secure. No. We are few and we are standing against the State of Israel. But I can’t do otherwise.”

On October 6, Ben Porat was out again with shepherds in the West Bank. The next day, her thoughts were with Jewish friends living in communities across from the Gaza Strip that were under attack by Hamas. “At the personal level it took me time to grasp things; I was paralyzed,” she says. Gradually reports started to reach her about a surge in violent incidents, raids on homes and threatening encounters in the West Bank. She decided to go out to accompany the locals again.

“I don’t do it out of pity or because I love Palestinians,” Ben Porat asserts. “I do it because it’s hard for me to accept what we [Israelis] are doing – it’s hard for me to accept what has become of us.”

* * *

The pressure being felt by the Palestinians living in Area C – which, as stipulated in the 1995 Oslo II Accord, comprises 60 percent of the West Bank and is under full Israeli control – is bearing fruit: Under the cover of the war in Gaza, particularly during its first weeks, mounting threats and actual acts of violence by Israeli soldiers and civilians have compelled residents of some 16 Palestinian communities – more than 1,000 people – to abandon their homes. These people are virtually defenseless in the face of attacks perpetrated under the apparent aegis of the Israel Defense Forces.

Alongside the Palestinian shepherds and farmers are Israeli activists who hope that their sheer presence will perhaps act as a shield against the settlers. In some cases, the activists stay with families around the clock. Since October 7, as the pressure on the local communities has grown, the activists have stepped up their work, which is organized by means of established nonprofits or even by ad hoc WhatsApp groups.

Who are the estimated few hundred people who venture out into the volatile West Bank, who spend nights in sleeping bags with families whose language they don’t speak, and even try to prevent attacks that don’t target them? What motivates ordinary people, including parents and pensioners, to tie their fate to that of total strangers whose way of life and culture is often quite foreign to them? And of all times now, in wartime?

Most of the activists fall into two age groups: Either they themselves are in their early 20s, or their children are in their early 20s. Both groups are pessimistic, but also espouse a worldview that centers around the here-and-now, in doing good – without thinking about a long-term political solution, without visions of either a binational state or two different states. They are not caught up in the booby-trapped discourse of “what should be done.” They are simply doing what they feel needs to be done.

Many of those interviewed here made a point of emphasizing that the story is not about them. That they are sacrificing their time and endangering themselves in order to tilt the trajectory of the story, but their sacrifice is nothing compared to the plight of the Palestinians. Many of the activists also stressed that the story is also not about violent settlers: Although it is the civilians, “hybrid” groups of settlers who try to pass themselves off as soldiers by donning uniforms, and settler-reservists called up after October 7 to guard their own communities who have all been running amok instead in the territories and pose a threat – it’s the army and the police that are permitting the rampages. It is they who are responsible for the disasters on the ground, and those that are yet to come.

The West Bank community of Marajat, in the Jordan Valley.Credit: David Bachar

Gil Alexander himself can’t really explain why he has never been afraid while out in the field helping Palestinians. Early last month he spent a whole night with shepherds for the first time. “I’m past the age of sleeping bags, but they were desperately looking for someone,” he relates. “I was sure things would be quiet, because for the previous three weeks nothing had happened.”

Al-Farisiya is a small pastoral community in the northern Jordan Valley – in a parallel universe, tourists and trekkers would stop there to enjoy the view and experience the local culture and way of life. A small wadi, a herd of goats on the now-verdant desert slopes, the distant ringing of cowbells amid quiet expanses. Since mid-October, residents have been subjected to harassment by settlers and IDF troops who have invaded their lands and threatened their lives, without any apparent pretext, demanding that they summarily pack up and leave. The women and children were sent elsewhere and the community of a few families was on the brink of falling apart. Israeli activists then established a full-time presence there, taking shifts. Al-Farisiya has survived – for now.

On December 14, Alexander and another activist, Sasha Povolotsky, were awakened in the lean-to of plastic sheeting and pipes they were sleeping in, alongside a muddy path, between cars with shattered windshields and a collection of rusty water troughs, by noise from the adjacent hill. It was 2 A.M. They went outside and encountered a tractor and a group of settlers who were throwing stones at the shepherds’ homes. Alexander was pepper-sprayed at zero range, cried out and collapsed – and was beaten by the settlers.

Alexander is still limping a bit when we meet. An unusual figure among the activists, and someone who began to volunteer with the Palestinians about four years ago, he immigrated to Israel from France 50 years ago, at age 20. “I grew up in a nonreligious, non-Zionist home,” he says. “We are five siblings who today are all religious, all Zionists, and we all settled in Israel. A model of failed education.” He met his wife, Esther, when both were involved in the Bnei Akiva youth moment.

“Since I arrived here, wherever I lived, on [religious kibbutz] Ein Hanatziv and afterward on Kibbutz Ma’aleh Gilboa, I was always considered the left-winger. My religious-Zionist viewpoint is that human rights take precedence over the wholeness of the Land of Israel.”

Alexander, who worked for decades in agriculture, says he’s always been a political animal, having been born in a political home. His father, who was born on France’s Independence Day, July 14, was a true French patriot who rejected Zionism. During World War II he fought in the Resistance. “‘Occupation is occupation is occupation,’ he would say.”

Alexander is a bereaved parent twice over: His eldest son, Amit, and another son, Yotam, both committed suicide during their army service, 13 years apart.

“That’s not related to what I do,” he says. “I can say that after a thing like that happens you try to find meaning in life in order to emerge from the abyss.” As part of that quest, Alexander volunteered at a suicide prevention nonprofit and drove Palestinians in need of medical treatment from Jenin to hospitals in Israel. He also does volunteer work with special needs children and elderly populations, and is part of the fringe Playback Theater group.

“Today I can say that I am a better and more whole person than I was,” he declared early last year at an event in support of families of fallen IDF soldiers. “I discovered how good it is for me when I do good things for others.”

Four years ago, friends told him about the attacks on Palestinian shepherds in the northern Jordan Valley, which he knows well because it’s effectively the backyard of his kibbutz. The first time he accompanied a shepherding family and their flock, they encountered three youths from a local settler outpost. They cursed and taunted the family. “I asked them why they were behaving like that. They said, ‘This is our God-given land and you have to get out of here now,'” Alexander recalls. Then someone named Zuriel, who established the outpost, showed up. “I said to him, ‘You know what? Invite me in for a cup of coffee.’ The next day I went over there with Esther.”

What did you talk about?

“About the fact that we are both Zionists, both Jews, both religiously observant, so what actually is it that separates us? We spoke for an hour about Judaism, about ideology.”

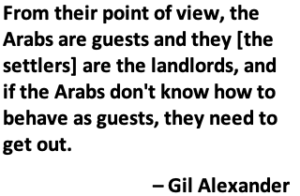

But the conversation hit an impasse. “From their point of view, the Arabs are guests and they [the settlers] are the landlords, and if the Arabs don’t know how to behave as guests, they need to get out.” For Alexander, it was a meaningful encounter. “It reinforced the understanding that I must express a different voice of religious Zionism.”

The ostensible seamline in his identity isn’t something new for Alexander. He attended the Tel Aviv peace rally on November 4, 1995 where Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated, but at the rally marking the first anniversary of that incident, he and Esther felt that people were crucifying them with their eyes because they were religious. During the second intifada, he helped members of the Four Mothers antiwar movement who wanted to meet with settlers. “At every encounter I felt how much easier it was for them to be with secular people than with me,” he admits.

“His presence there makes them angry,” Esther says. “A religious person riles them a lot more, because they see him as ‘one of us’ and not one of the secular people, to whom the religious people assert, ‘It’s written in the Torah,’ but then they [the secular people] don’t know what to say.” Alexander agrees: “Religious people often say, ‘You’re left-wing, so how can you be religious? Take off the kippa, you’re a fake believer.'” Many observant people who know about his activism don’t speak to him.

What are your relations with the shepherds like?

“I feel a great deal of appreciation from them; sometimes I feel that they also respect me because I am religious. They see the kippa and the tzitzit [prayer fringes], and that is a corrective experience. There’s one shepherd who speaks excellent Hebrew – every conversation with him is like oxygen for me. I also had a sort of opposite experience with another shepherd. He started to pray, and the time came for mincha [afternoon prayers in Judaism], so we prayed together. Then he said, ‘Well, your religion is not the true religion. Only Islam is the true religion.’ Like that, with a smile, but it was like being stabbed in the heart.”

The same December night her friend Gil Alexander was attacked in Al-Farisiya, Yifat Mehl, at home in Yokne’am, in northern Israel, read a spate of urgent WhatsApp messages from a group of activists, got into her car and drove straight to the Palestinian enclave. She got there at 4 A.M. “They’re my friends,” she says, of the residents.

For two years, Mehl would go out twice a month with the shepherds to their grazing areas in the northern Jordan Valley – but since the war broke out, she’s been going every week. We’re sitting not far from where the attack on Alexander took place, taking refuge from the glaring afternoon sun in the shade of a hut. Opposite us is the flock of sheep safely returning from pasturing.

Last month, Mehl experienced a fraught moment with the same flock. “We were in the field, a lovely place with top-quality meadow grass,” she relates. “Suddenly a force of 12 soldiers appeared, all of them residents of the nearby settlement who had likely been mobilized in connection with the war, on an emergency basis. One of them hunched behind a bush and aimed a rifle at me. ‘What are you doing?!’ I shouted. I think he had some sort of strange urge to feel like a real fighter, or something like that.”

The soldiers approached and ordered them to leave, claiming the land was under the jurisdiction of the Shadmot Mehola settlement nearby. “There was nothing there: a shepherd with three activists accompanying him to a place where he’s pastured for years – and sheep. They told us that maybe the man was a terrorist, who might ‘do an October 7’ on us. Armed from head to foot, with all the usual weapons and the helmets and the camouflage nets.”

A week later, Mehl and a few other Israelis accompanied the same man as he set out to plow a field that he owns. Again soldiers suddenly showed up, this time with a settler, who also serves as a territorial defense officer in the reserves. They alleged that the Palestinian had crossed over the boundaries of his own land, into an area declared to be a nature reserve. The armed protectors of nature told him to accompany them outside his private property. When he did so, they declared the area he had crossed into a closed military zone, impounded his tractor, handcuffed and blindfolded him, and took him into custody for eight hours. Mehl, who refused to leave, was detained with the shepherd.

Since October 7, she says, what she’s noticed in particular is the even closer collaboration between the army and the settlers who are serving in the army or the civilians who try to look as if they do.

“The army succumbing to the caprices of the settlers – that is the story. It’s no longer the old-style violence, when they came and forced the flocks to scatter. We fought against that, but they [the settlers] no longer suffice with that kind of ‘simple’ violence. They are pulling the strings of the army like it’s their marionette. During the war, 13 reservist infantrymen, young, talented, show up to arrest a farmer with a tractor who might have gone over the boundaries of his property and entered what’s been called a nature reserve.”

Mehl is a project manager in a civil society organization; she has three sons, aged 20 to 28. She grew up in a “very Zionist, even right-wing,” home in Nahariya, and served, “whole-heartedly,” as an education noncom in an artillery battalion. The fact that her father died before she embarked on her activism has probably spared the family a full-blown crisis. Her mother is worried, sad. “She doesn’t think I am the one who should be doing this.”

Why are you the one who should be doing it?

“That’s how I was raised, no? Zionism itself educated me to stand up, to dedicate myself, to deride attempts to shirk one’s duty. That always spoke to me, the stories of heroism and boldness and camaraderie – to this day that’s what drives me. It’s just the content that has changed. Without the acts of rescue during the Holocaust, what would we have done? How would we have arisen from it, if you don’t have these stories of people who did what they could with whatever abilities they had? It might sound like too much pathos, but really, how can we tolerate humanity without these acts? Even if the struggle fails, at least the stories will be there. Within the big story there will be more chapters.”

Is it worth the price you are paying?

“What price am I paying? What – my crappy time? One of the reasons I’m here is that I’m not paying enough of a price. So I come again and again. When will I be paying enough? When will I be able to free myself of this guilt? I really don’t know. I sometimes think that only if I experience a real blow will I be able to calm down.”

Heartrending howls cut off our conversation. A shepherd’s child passes by, dragging a puppy who’s being strangled by its leash. Mehl winces. How well does she know the people she’s protecting? Their heart’s desires, their yearnings, even their conceptions about her presence here? Everything she was or was not familiar with faced a test on October 7. “It was a horrendous day,” she says. “The balance of forces was totally reversed. I didn’t know whether we even had an army.”

And you showed up here?

“On October 7 I felt very Jewish and very Israeli, and I thought that maybe I wouldn’t go back. Let them go to hell. My collective identity was suddenly reinforced. I started to move toward insularity, toward withdrawing within the shared pain, toward what’s supposed to be my real identity. Maybe I was afraid that this would happen to me, and that if I forced myself to think about things rationally, it would stop the emotional process I’m undergoing. Maybe that’s the reason that at 6 A.M. on October 8 I was on the road.

“I don’t know why I went,” she continues. “We didn’t even go with the shepherds to their pastures – who even left the house? We simply began to wander among the different communities. These people need to have [access to] water, and the village has a gate, and the army decides when that gate will be opened. That day, the army locked the gate and they ran out of water. We approached them [the soldiers] and they told us, ‘You’re not ashamed, on a day like this? Why do you even care about them?’ I’m not indifferent to that at all. My reference group is still Israel and Israelis, first and foremost.”

The friction grew more acute as she traveled around on October 8. Mehl says she sensed a sort of frenzy in the air. The radio was blaring and the announcer sounded jubilant. “They [the Palestinians] didn’t tell me they were happy, but there was something in the air,” she recalls. “I was flabbergasted.”

How do you feel about the fact that the October 7 events might have been what they were actually wishing for?

“I don’t think that’s right, that’s not true. A few days later I understood that the joy was over a victory, over an opportunity they aren’t familiar with: to feel on top for once. Not all the details that we [Israelis] already knew at that point were known to them.”

Doesn’t this dissonance accompany you when you accompany them?

“No. I wouldn’t say they rejoiced. These people here” – she points to the makeshift hut near us – “I guarantee you that they will do everything to protect us.”

Amid rusting hulks of cars, putrefying garbage and meager shacks inhabited by members of the Kaabana Bedouin tribe in Wadi Kelt, on the way to Jericho, there are a few new tin panels and wooden beams. Yael Moav gets out of her car with a big smile and hands out colorful balloons to the children who gather around her.

“People who don’t know Arabic think I speak the language fluently, but for those who do know it, I sound a little like someone from a sketch on [the satirical show] ‘A Wonderful Country,’ about the left-winger who goes out into the field. They also call me Razala [yael, or ibex, in Arabic],'” she says. “I’m a little like a caricature of a left-wing activist, with white hair, not so well-groomed. Wait till you see me with false eyelashes.”

Moav, who has two children, pulls out a photo from her previous incarnation. “I was the queen of belly dancers in Jerusalem, I danced on tables, I made the gossip columns,” she says, laughing. ‘Even I find it hard to believe.” Ten years ago she closed the studio she’d founded and managed, did a tour guide course and began taking a special interest in geopolitics. “I could do tourism for Evangelical people and make four times as much, but almost all the tourism I do is political.”

Osama Kaabana gives us a short tour of the old and new dwellings. The problems started in mid-October, he says. Masked soldiers, whom he assumed were settlers because of their tzitzit, showed up one night. They blocked the access road to the little Bedouin enclave and threatened to kill him and burn his home down if he didn’t leave. “What could we do?” he sighs. He himself demolished the huts, some of which have since been rebuilt. Soldiers continued to show up at night, sometimes entering homes repeatedly with blindingly bright flashlights, conducting pointless searches, frightening the children.

The peak came at the end of November, when a few dozen settlers ran wild one night, smashed windshields, shattered solar panels and destroyed animal pens. A video shot by Kaabana that night shows the marauders dancing in a frenzy outside his home and singing ecstatically, “And the heart has been ignited, it burns with love… In the distance can be heard the shofar of redemption.”

Kaabana sought help from an NGO called Friends of Jahalin (the name of another Bedouin tribe). The next day, activists from the group, among them Yael Moav, arranged to take shifts around the clock at the site. They also raised funds to rebuild the demolished structures in coordination with the military government’s Civil Administration.

Friends of Jahalin, founded in 2017 ahead of the government-ordered evacuation of the Bedouin village of Khan al-Ahmar, east of Jerusalem, is a sort of anomaly in the activist landscape. “It’s a nonpolitical group, that’s the lovely story here,” Moav says. “We are absolutely not a left-wing group. There’s a broad range of views among the members, including settlers. We try to do everything by means of dialogue, and that’s where our strength lies, I’d say. We cooperate with the police and the army, which is how we were able to rebuild the shacks. It’s amazing. It’s all thanks solely to those connections.”

In one incident last summer, the security chief of the Kfar Adumim settlement, Avichai Shorshan, detained a local 10-year-old Bedouin boy. Moav saw a picture of the wailing child, cowering at Shorshan’s feet on a rocky slope. “The boy’s mother was in an advanced stage of pregnancy, the goats had run away and the boy had run to fetch them back. This was hundreds of meters away from the settlement. The security man showed up and grabbed him violently,” she relates. “I called one of our activists in Kfar Adumim, and he went to the site. He spoke with Shorshan and calmed things down. No other activist group does those things.”

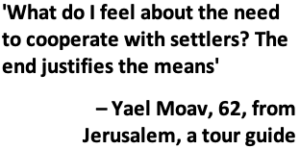

How do you feel about the need for your group to cooperate with the settlers?

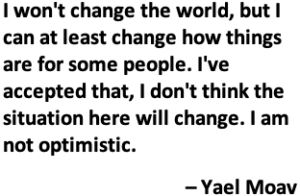

“The end justifies the means, let’s put it that way. If a peace plan involving the evacuation of settlements were on the agenda, maybe I would behave differently, but I see that the war is pretty much lost. If you can’t fight ’em, join ’em. It comes from yielding, from understanding that I won’t change the world, but that I can at least change how things are for some people. I’ve accepted that, I don’t think the situation here will change. I am not optimistic.”

Moav has impressive Zionist lineage. Her grandmother was the beloved niece of the famous early-Zionist poet Rachel (Bluwstein), her family was among the founders of Kibbutz Afikim, and her father attended Kadoorie, the iconic agricultural school, fought in the pre-state Palmah commandos and was the director of the Volcani agricultural institute. Before we set out to visit the Kaabani tribe, Moav prepared breakfast for her son, who was on furlough from reserve service.

Besides her activity in Friends of Jahalin – which, she stresses, should be defined as “not left, not right, maybe humanitarian” – Moav is also involved in other nonpolitical activities involving Palestinians, including driving children from the West Bank for medical treatment in Israel. She also established (with a friend, Galia Chai) a cottage industry of women in Khan al-Ahmar who create embroidered dolls and sell them. “We’ve saved the tribe here, but others tribes are still being destroyed,” she says. “I am not naïve. I also do it for my children, so they will see this example. To know that at least I tried.”

In early December, Hillel Levi Faur found himself walking in the rain, in the dark, in the South Hebron Hills. He’d been summoned to a Jerusalem hospital because of a family medical problem, and had been compelled to leave the small, isolated Bedouin community where he had been staying. “It’s really scary to wander around there after dark, certainly on foot,” he says. Levi Faur and his fellow Israeli activists are trying to help protect residents of eight different communities in the hills by living with them, accompanying them, for various periods of time. When the war broke out, the army blocked the access roads to some of them, so activists and others resort to walking.

In early December, Hillel Levi Faur found himself walking in the rain, in the dark, in the South Hebron Hills. He’d been summoned to a Jerusalem hospital because of a family medical problem, and had been compelled to leave the small, isolated Bedouin community where he had been staying. “It’s really scary to wander around there after dark, certainly on foot,” he says. Levi Faur and his fellow Israeli activists are trying to help protect residents of eight different communities in the hills by living with them, accompanying them, for various periods of time. When the war broke out, the army blocked the access roads to some of them, so activists and others resort to walking.

“These are people who are living with anxiety about their lives,” Levi Faur says. “In the house where I’m staying, there are two televisions turned on nonstop. One is tuned to Al Jazeera [which broadcasts from Qatar], which is stressful in itself, and the other displays the feed from six closed circuit cameras filming every direction from the house.”

One night, Levi Faur switched places with the father of the family and slept in the improvised control room. “You’re looking at the images from the cameras all the time and not really sleeping, because everything is on all the time. In the morning he said, ‘Walla, that’s the first time I’ve slept in the past three weeks.'”

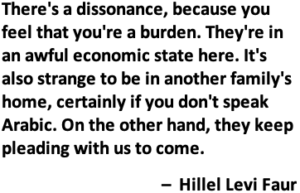

About 100 volunteers belong to a social media group, whose name is roughly translated as Presence in Hard Times, which was set up after October 7 to arrange for an ongoing activist presence in the volatile South Hebron Hills. “The daily routine is pretty static, we don’t do much, it’s a defensive presence,” Levi Faur explains. “Each family that hosts us assumes the cost of housing us, of our meals. We activists are pretty frugal anyway. Our approach is that we are donating our time, and anyway there are boomers who donate money. There’s a dissonance, because you feel that you’re a burden. They’re in an awful economic state here. It’s also strange to be in another family’s home, certainly if you don’t speak Arabic. On the other hand, they keep pleading with us to come. There are communities that make you feel bad if you don’t show up for a week or two. They say, ‘We can’t sleep.’ It’s terrible, having those conversations.”

You take all this home with you?

“Absolutely. Obviously.”

According to the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem, six of the 16 West Bank communities that have been forced out of their homes due to attacks by soldiers and settlers, under the cover of war, lived in the South Hebron Hills – more than 350 souls, all told. All the testimonies speak of live fire, threats of murder and violent raids by settlers, soldiers and settler-soldiers. Footage shot in October in the village of Al-Tuwani shows one intruder dressed in civilian clothes and armed with a rifle, approaching a local resident, pushing him and shooting him from close range.

“You never come out of here with a good feeling,” Levi Faur says.

Is there something here that energizes you nevertheless?

“Yes, there are some sweet little girls who ask about me all the time, and it does me good to joke around with them and teach them a little English. But no, there is no uplifting experience here. There isn’t something that you need to go at the end of some magazine article. What drives me? A feeling of guilt. Even when they thank me, it doesn’t sit right. My feeling is that this is the minimum I am required to do.”

Levi Faur grew up in a family of academics “from the left-wing Jerusalem bubble.” His mother, Naomi Sussman, herself a veteran left-wing activist, wrote a column recently in Haaretz Hebrew edition about her experiences with him in Masafer Yatta before the war broke out.

“I was born with my eyes open,” he says. “I had a lot of doubts about doing army service, and one way or another was caught up in the web of leftist-Zionist education.” He attended an army preparatory program and served as a paramedic in the IDF. He admits to sometimes empathizing with the conscript soldiers he meets, but no genuine dialogue develops with them. “They really look at you with eyes filled with poison and hatred at a level that’s hard to describe,” he says.

What did you learn here that you didn’t know before?

“It’s impossible to understand from media reports the despair and the fear with which these people live. It’s a life lived in dread, with the feeling that there is no one to protect you. A child in Masafer Yatta who hears the word mustawteen, settler, is seized by anxiety. You see a girl of 5 or 6 with fear in the eyes that is hard to contain. Every child there has posttraumatic stress disorder. They see us [Israelis] as violent people in a way you’re not capable of describing. They don’t see us as we see ourselves.”

The village of Al-Tuwani is at the entrance to Masafer Yatta, a cluster of hamlets in the South Hebron Hills, and it is a hub of activism. One day in December at least 10 Israelis could be seen wandering along on its steep roads and paths, on their way to and from the small communities. Most of the activists are young, and from the way they are dressed, the hyperactivity they exude and the spectacular landscapes, one could imagine for a moment that this is a happy village of backpackers.

The village of Al-Tuwani is at the entrance to Masafer Yatta, a cluster of hamlets in the South Hebron Hills, and it is a hub of activism. One day in December at least 10 Israelis could be seen wandering along on its steep roads and paths, on their way to and from the small communities. Most of the activists are young, and from the way they are dressed, the hyperactivity they exude and the spectacular landscapes, one could imagine for a moment that this is a happy village of backpackers.

Hillel Garmi, 24, shows me the room in a building in Al-Tuwani where the activists sleep. Sleeping bags, maps on the wall, a computer corner and Hebrew-Arabic and English-Arabic dictionaries on a messy bookshelf.

“The most meaningful moment for me was on October 7,” he says. “We were here by chance that morning, and tension began to develop pretty quickly between Al-Tuwani and Havat Maon [an adjacent settlement]. We went and stood there with cameras, to help make sure nothing would happen.”

“Nothing happening” is the chief goal of the Israeli volunteers’ defensive presence. But the locals started to congregate at the edge of the village after they spied a settler on an all-terrain vehicle in a grove nearby; soldiers who arrived told them to disperse. The tension kept growing.

Garmi: “I don’t think I’ve ever seen such furious soldiers. There was no one to talk to at that moment, for them we were the embodiment of Hamas. At one stage they started to march toward us, getting really edgy, cursing us – ‘We’ll f–k you over,’ ‘Get out of here.’ We kept trying to keep things as calm as possible.”

This volatile state of affairs continued for a few hours, but there was no explosion, he adds: “At a certain stage they threatened that if we didn’t get out of there they would arrest us. To be arrested on October 7 would have been a very scary scenario.”

On that day, Garmi happened to be in Al-Tuwani with a friend from Kibbutz Be’eri, which was then under a brutal Hamas attack. “We stood there at 7 A.M., four leftists alone on a godforsaken hill in the middle of nowhere, and within five minutes two military jeeps show up. And then my friend sat there all day long talking to his mother, who was in a safe room on the kibbutz, and there were no soldiers and no one coming to rescue her,” he recalls. “It was shocking.”

Mathematics, says Garmi, who is from Misgav, in the north, “is the only thing that I’m certain that will continue to interest me my whole life.” He has youthful features, but there’s something about him that hints that there’s more to him than meets the eye. He refused to do army service and spent three months in prison, then did a year of National Service instead, working with at-risk youth. He underwent his baptism of fire in activism three years ago, while spending several months in the South Hebron Hills.

He describes how, in a pasture not far from Havat Maon, he saw a group of Arab children picking akoub, a spiny plant that’s used in cooking, who were getting close to the settlement. Shortly afterward, a large number of soldiers gathered around one of the homes in a neighboring village. “We saw them, these big soldiers, simply dragging four children from that group, into army vehicles. I don’t remember exactly what story the soldiers had been told by the Havat Maon settlers, but the troops activated some kind of procedure involving the penetration of a settlement, something like that.

“One of the children was walking near me as the arrests were taking place. I didn’t understand why he hadn’t been taken away with the others. The jeeps were already moving out, and he asked for my phone so he could call his father and tell him that all his friends had been detained. And then, as he was saying goodbye, an army jeep pulled up next to us. An officer got out and bent over, the way you do to pick up a child, grabbed the boy, stuck him in the vehicle and drove off. There was a feeling of total helplessness, also because, besides the children, I and the activist who was with me were the only ones who had witnessed the whole incident from beginning to end.”

Since the war began, Garmi says he’s noted a change in regard to the cameras, almost the only weapons the activists have. “A new era started. Throughout the first weeks, the soldiers or the settlers in uniforms simply confiscated or broke every cellphone and camera they saw.” Despite this, the activists’ struggle is based on steadfastness, Garmi asserts. The soldiers in the area change, the settlers exert pressure, in general the law is vague or is not enforced, and within that complex situation, a status quo is being created. The consistent presence of the activists, their persistence, he says, constitutes an important element in shaping the status quo.”

One inch and another inch – is there a horizon for this struggle?

“I don’t see much hope, but there are a few people there that I already feel are my friends, and I even feel a sense of commitment toward them to continue coming and to not abandon them in their struggle. Over time I’ve also developed an approach that says: This question of the horizon is about what will happen in eternity, a little like Jewish messianism. Who will win in the end? I don’t know, and it doesn’t interest me all that much, because in the meantime we’ve been living in the midst of this struggle for decades. People are born and die in the course of this struggle. So, if we are humanists, and what is important for us is human happiness and suffering, we must see how we can make the lives of these people better.”

Thanks, what a collection of harrowing stories showing the bravery of some Israelis and the deep despair of all Palestinians. It is apparent that the ‘left’ activists who have rejected the ‘occupation’ aspect of Zionism i.e. the vicious side, still consider themselves to be Zionists. They don’t appear to recognise that Zionism can’t be one without the other. It shows how deeply Zionism has corrupted Judaism and that ‘left Zionists’ are not Zionists at all, even though they believe they are.

Can someone let us know how we can support these heroic people? Maybe JVL could formally adopt them and do a fundraiser.

Another account of indigenous people persecuted by entitled incomers.

The political zionist dogma that the land has been given to Israelis by God is not factually or historically based and is highly extremist. It is the underlying opinion of the extremist Israeli government. It is also shown by it being the expressed ideology of the Israeli state representative in Britain. This is not commented on by British establishment politicians or mass media.

I also recognise and applaud the good Israelis who are unselfishly putting themselves into conflict with their establishment to try to save Palestinians.

Anyone can submit evidence to the ICC prosecutor.

He can be reached at this email.

https://otplink.icc-cpi.int/

https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/otp/otp-contact

He has jurisdiction in Palestine.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/nov/10/law-israel-hamas-international-criminal-court-icc

Witness, and staying alive to perform it, is probably the most altruistic survivor strategy there is. Well-documented in Terrence des Pres’ classic book, The Survivor, chapter II, “The Will to Bear Witness”, p 27.

https://archive.org/details/survivoranatomyo00desp/page/n15/mode/2up?view=theater

These heroes are the new righteous, and thanks to the reporter and Haaretz for publishing this most important story.

David Shonfield,

B’Tselem, mentioned in the story, is the organization of record of Israelis and Palestinians working together to video the assault by settlers on Palestinians. You can contribute on their website:

https://www.btselem.org/

And view their videos on Twitter, very much worth a follow:

@btselem

It doesn’t appear as if these folks are affiliated with B’Tselem but you never know.

If ‘all that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good people to do nothing’, then this is a case of good, brave people going above and beyond the call of duty. They are an inspiration to us all, and I thank them from the bottom of my heart. They are fighting for all of us.

Shalom-Salam-Peace

Dear sisters and brothers!

Your exceptional commitment to peace and justice touches my heart. The essence of all religions and humanism is love shared with other human beings. You are wonderful witnesses in word and deed. With you, there is not us and them, but one great human family. I admire you in solidarity

Thank you so much! -Michel Barrett from Quebec in Canada