The Guardian’s abject failure to speak out

JVL Introduction

A massive assault on freedom of speech is underway as Julian Assange is hung out to dry as an example to all that it is safer to stick to what the corporates want you to report.

You’d think liberal newspapers like the Guardian and the New York Times would be rushing to his defence.

Instead they are allowing journalism that exposes unwanted truths to be redefined as “espionage”. Colluding with the US government has got them off the hook.

Here Jonathan Cook exposes and explains the shameful role of the liberal media.

This article was originally published by Jonathan Cook Blog on Tue 22 Sep 2020. Read the original here.

The US is using the Guardian to justify jailing Assange for life. Why is the paper so silent?

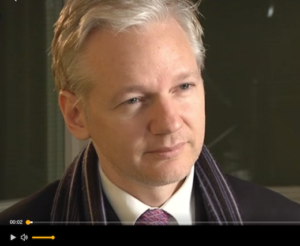

Julian Assange is not on trial simply for his liberty and his life. He is fighting for the right of every journalist to do hard-hitting investigative journalism without fear of arrest and extradition to the United States. Assange faces 175 years in a US super-max prison on the basis of claims by Donald Trump’s administration that his exposure of US war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan amounts to “espionage”.

The charges against Assange rewrite the meaning of “espionage” in unmistakably dangerous ways. Publishing evidence of state crimes, as Assange’s Wikileaks organisation has done, is covered by both free speech and public interest defences. Publishing evidence furnished by whistleblowers is at the heart of any journalism that aspires to hold power to account and in check. Whistleblowers typically emerge in reaction to parts of the executive turning rogue, when the state itself starts breaking its own laws. That is why journalism is protected in the US by the First Amendment. Jettison that and one can no longer claim to live in a free society.

Aware that journalists might understand this threat and rally in solidarity with Assange, US officials initially pretended that they were not seeking to prosecute the Wikileaks founder for journalism – in fact, they denied he was a journalist. That was why they preferred to charge him under the arcane, highly repressive Espionage Act of 1917. The goal was to isolate Assange and persuade other journalists that they would not share his fate.

Assange explained this US strategy way back in 2011, in a fascinating interview he gave to Australian journalist Mark Davis. (The relevant section occurs from minute 24 to 43.) This was when the Obama administration first began seeking a way to distinguish Assange from liberal media organisations, such as the New York Times and Guardian that had been working with him, so that only he would be charged with espionage.

Assange warned then that the New York Times and its editor Bill Keller had already set a terrible precedent on legitimising the administration’s redefinition of espionage by assuring the Justice Department – falsely, as it happens – that they had been simply passive recipients of Wikileaks’ documents. Assange noted (40.00 mins):

If I am a conspirator to commit espionage, then all these other media organisations and the principal journalists in them are also conspirators to commit espionage. What needs to be done is to have a united face in this.

During the course of the current extradition hearings, US officials have found it much harder to make plausible this distinction principle than they may have assumed.

Journalism is an activity, and anyone who regularly engages in that activity qualifies as a journalist. It is not the same as being a doctor or a lawyer, where you need a specific professional qualification to practice. You are a journalist if you do journalism – and you are an investigative journalist if, like Assange, you publish information the powerful want concealed. Which is why in the current extradition hearings at the Old Bailey in London, the arguments made by lawyers for the US that Assange is not a journalist but rather someone engaged in espionage are coming unstuck.

Corporate journalists have barely bothered to cover Assange’s trial. But while they doze, the US has changed its argument, as ex-ambassador Craig Murray reports. Now the US is threatening to lock up other journalists for espionage if they expose its crimes https://t.co/4dpYUQ0EAZ

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 16, 2020

My dictionary defines “espionage” as “the practice of spying or of using spies, typically by governments to obtain political and military information”. A spy is defined as someone who “secretly obtains information on an enemy or competitor”.

Very obviously the work of Wikileaks, a transparency organisation, is not secret. By publishing the Afghan and Iraq war diaries, Wikileaks exposed crimes the United States wished to keep secret.

Assange did not help a rival state to gain an advantage, he helped all of us become better informed about the crimes our own states commit in our names. He is on trial not because he traded in secrets, but because he blew up the business of secrets – the very kind of secrets that have enabled the west to pursue permanent, resource-grabbing wars and are pushing our species to the verge of extinction.

In other words, Assange was doing exactly what journalists claim to do every day in a democracy: monitor power for the public good. Which is why ultimately the Obama administration abandoned the idea of issuing an indictment against Assange. There was simply no way to charge him without also putting journalists at the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Guardian on trial too. And doing that would have made explicit that the press is not free but works on licence from those in power.

Media indifference

For that reason alone, one might have imagined that the entire media – from rightwing to liberal-left outlets – would be up in arms about Assange’s current predicament. After all, the practice of journalism as we have known it for at least 100 years is at stake.

But in fact, as Assange feared nine years ago, the media have chosen not to adopt a “united face” – or at least, not a united face with Wikileaks. They have remained all but silent. They have ignored – apart from occasionally to ridicule – Assange’s terrifying ordeal, even though he has been locked up for many months in Belmarsh high-security prison awaiting efforts to extradite him as a spy. Assange’s very visible and prolonged physical and mental abuse – both in Belmarsh and, before that, in the Ecuadorian embassy, where he was given political asylum – have already served part of their purpose: to deter young journalists from contemplating following in his footsteps.

Even more astounding is the fact that the media have taken no more than a cursory interest in the events of the extradition hearing itself. What reporting there has been has given no sense of the gravity of the proceedings or the threat they pose to the public’s right to know what crimes are being committed in their name. Instead, serious, detailed coverage has been restricted to a handful of independent outlets and bloggers.

Most troubling of all, the media have not reported the fact that during the hearing lawyers for the US have abandoned the implausible premise of their main argument that Assange’s work did not constitute journalism. Now they appear to accept that Assange did indeed do journalism, and that other journalists could suffer his fate. What was once implicit has become explicit, as Assange warned: any journalist who exposes serious state crimes now risks the threat of being locked away for the rest of their lives under the draconian Espionage Act.

The BBC’s Kuenssberg and ITV’s Peston haven’t mentioned Assange for years, even as his extradition hearing – our generation’s Dreyfus Trial – is under way.

It should be proof, if more were needed, that these people aren’t journalists, they are courtiers of the British state https://t.co/2ybAEkoAhz

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 8, 2020

This glaring indifference to the case and its outcome is extremely revealing about what we usually refer to as the “mainstream” media. In truth, there is nothing mainstream or popular about this kind of media. It is in reality a media elite, a corporate media, owned by and answerable to billionaire owners – or in the case of the BBC, ultimately to the state – whose interests it really serves.

The corporate media’s indifference to Assange’s trial hints at the fact that it is actually doing very little of the sort of journalism that threatens corporate and state interests and that challenges real power. It won’t suffer Assange’s fate because, as we shall see, it doesn’t attempt to do the kind of journalism Assange and his Wikileaks organisation specialise in.

The indifference suggests rather starkly that the primary role of the corporate media – aside from its roles in selling us advertising and keeping us pacified through entertainment and consumerism – is to serve as an arena in which rival centres of power within the establishment fight for their narrow interests, settling scores with each other, reinforcing narratives that benefit them, and spreading disinformation against their competitors. On this battlefield, the public are mostly spectators, with our interests only marginally affected by the outcome.

A journalist due to testify at Julian Assange’s extradition hearing makes a very pertinent point. This is the biggest attack on press freedom in our lifetimes. Why are UK editors not demanding to be heard at the Old Bailey? Where are they? Where is the Guardian? https://t.co/fFRFvGpYdi

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 8, 2020

Gatekeeper role under threat

For a brief while, this mutual dependency just about worked. But only for a short time. In truth, the liberal corporate media is far from committed to a model of unmediated, whole-truth journalism. The Wikileaks model undermined the corporate media’s relationship to the power establishment and threatened its access. It introduced a tension and division between the functions of the political elite and the media elite.

Those intimate and self-serving ties are illustrated in the most famous example of corporate media working with a “whistleblower”: the use of a source, known as Deep Throat, who exposed the crimes of President Richard Nixon to Washington Post reporters Woodward and Bernstein back in the early 1970s, in what became known as Watergate. That source, it emerged much later, was actually the associate director of the FBI, Mark Felt.

Far from being driven to bring down Nixon out of principle, Felt wished to settle a score with the administration after he was passed over for promotion. Later, and quite separately, Felt was convicted of authorising his own Watergate-style crimes on behalf of the FBI. In the period before it was known that Felt had been Deep Throat, President Ronald Reagan pardoned him for those crimes. It is perhaps not surprising that this less than glorious context is never mentioned in the self-congratulatory coverage of Watergate by the corporate media.

But worse than the potential rupture between the media elite and the political elite, the Wikileaks model implied an imminent redundancy for the corporate media. In publishing Wikileaks’ revelations, the corporate media feared it was being reduced to the role of a platform – one that could be discarded later – for the publication of truths sourced elsewhere.

The undeclared role of the corporate media, dependent on corporate owners and corporate advertising, is to serve as gatekeeper, deciding which truths should be revealed in the “public interest”, and which whistleblowers will be allowed to disseminate which secrets in their possession. The Wikileaks model threatened to expose that gatekeeping role, and make clearer that the criterion used by corporate media for publication was less “public interest” than “corporate interest”.

In other words, from the start the relationship between Assange and “liberal” elements of the corporate media was fraught with instability and antagonism.

The corporate media had two possible responses to the promised Wikileaks revolution.

One was to get behind it. But that was not straightforward. As we have noted, Wikileaks’ goal of transparency was fundamentally at odds both with the corporate media’s need for access to members of the power elite and with its embedded role, representing one side in the “competition” between rival power centres.

I bet Assange is stuffing himself full of flattened guinea pigs. He really is the most massive turd.

— suzanne moore (@suzanne_moore) June 19, 2012

The corporate media’s other possible response was to get behind the political elite’s efforts to destroy Wikileaks. Once Wikileaks and Assange were disabled, there could be a return to media business as usual. Outlets would once again chase tidbits of information from the corridors of power, getting “exclusives” from the power centres they were allied with.

Put in simple terms, Fox News would continue to get self-serving exclusives against the Democratic party, and MSNBC would get self-serving exclusives against Trump and the Republican Party. That way, everyone would get a slice of editorial action and advertising revenue – and nothing significant would change. The power elite in its two flavours, Democrat and Republican, would continue to run the show unchallenged, switching chairs occasionally as elections required.

From dependency to hostility

Typifying the media’s fraught, early relationship with Assange and Wikileaks – sliding rapidly from initial dependency to outright hostility – was the Guardian. It was a major beneficiary of the Afghan and Iraq war diaries, but very quickly turned its guns on Assange. (Notably, the Guardian would also lead the attack in the UK on the former leader of the Labour party, Jeremy Corbyn, who was seen as threatening a “populist” political insurgency in parallel to Assange’s “populist” media insurgency.)

Assange possibly even the biggest arsehole in Knightsbridge. And what a field that is

— Marina Hyde (@MarinaHyde) May 19, 2017

Despite being widely viewed as a bastion of liberal-left journalism, the Guardian has been actively complicit in rationalising Assange’s confinement and abuse over the past decade and in trivialising the threat posed to him and the future of real journalism by Washington’s long-term efforts to permanently lock him away.

There is not enough space on this page to highlight all the appalling examples of the Guardian’s ridiculing of Assange (a few illustrative tweets scattered through this post will have to suffice) and disparaging of renowned experts in international law who have tried to focus attention on his arbitrary detention and torture. But the compilation of headlines in the tweet below conveys an impression of the antipathy the Guardian has long harboured for Assange, most of it – such as James Ball’s article – now exposed as journalistic malpractice.

The Guardian: Fake news and hostility toward Assange in 44 headlines. #DumpTheGuardian https://t.co/jwl5ZbEOL7

— FiveFilters.org ⏳ (@fivefilters) April 19, 2019

The Guardian’s failings have extended too to the current extradition hearings, which have stripped away years of media noise and character assassination to make plain why Assange has been deprived of his liberty for the past 10 years: because the US wants revenge on him for publishing evidence of its crimes and seeks to deter others from following in his footsteps.

In its pages, the Guardian has barely bothered to cover the case, running superficial, repackaged agency copy. This week it belatedly ran a solitary opinion piece from Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s former leftwing president, to mark the fact that many dozens of former world leaders have called on the UK to halt the extradition proceedings. They appear to appreciate the gravity of the case much more clearly than the Guardian and most other corporate media outlets.

167 politicians, including past & present heads of state, back our appeal to UK government to bring an end to Julian Assange’s extradition proceedings & grant him his long overdue freedom:https://t.co/dUsokJWmbX

We @Lawyers4Assange say the politico-legal show must not go on.

— Lawyers for Assange (@Lawyers4Assange) September 20, 2020

But among the Guardian’s own columnists, even its supposedly leftwing ones like Gorge Monbiot and Owen Jones, there has been blanket silence about the hearings. In familiar style, the only in-house commentary on the case so far is yet another snide hit-piece – this one in the fashion section written by Hadley Freeman. It simply ignores the terrifying developments for journalism taking place at the Old Bailey, close by the Guardian’s offices. Instead Freeman mocks the credible fears of Assange’s partner, Stella Moris, that, if Assange is extradited, his two young children may not be allowed contact with their father again.

Freeman’s goal, as has been typical of the Guardian’s modus operandi, is not to raise an issue of substance about what is happening to Assange but to score hollow points in a distracting culture war the paper has become so well-versed in monetising. In her piece, entitled “Ask Hadley: ‘Politicising’ and ‘weaponising’ are becoming rather convenient arguments”, Freeman exploits Assange and Moris’s suffering to advance her own convenient argument that the word “politicised” is much misused – especially, it seems, when criticising the Guardian for its treatment of Assange and Corbyn.

The paper could not make it any plainer. It dismisses the idea that it is a “political” act for the most militarised state on the planet to put on trial a journalist for publishing evidence of its systematic war crimes, with the aim of locking him up permanently.

Shameful but not surprising. This is the sum total of the @guardian‘s “coverage” during Julian Assange’s extradition hearing. Including a hit piece. #DumpTheGuardian #FreeAssange pic.twitter.com/Vd9tpr2Iuo

— Bean🔥 (@SomersetBean) September 16, 2020

Password divulged

The Guardian may be largely ignoring the hearings, but the Old Bailey is far from ignoring the Guardian. The paper’s name has been cited over and over again in court by lawyers for the US. They have regularly quoted from a 2011 book on Assange by two Guardian reporters, David Leigh and Luke Harding, to bolster the Trump administration’s increasingly frantic arguments for extraditing Assange.

When Leigh worked with Assange, back in 2010, he was the Guardian’s investigations editor and, it should be noted, the brother-in-law of the then-editor, Alan Rusbridger. Harding, meanwhile, is a long-time reporter whose main talent appears to be churning out Guardian books at high speed that closely track the main concerns of the UK and US security services. In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that I had underwhelming experiences dealing with both of them during my years working at the Guardian.

Normally a newspaper would not hesitate to put on its front page reports of the most momentous trial of recent times, and especially one on which the future of journalism depends. That imperative would be all the stronger were its own reporters’ testimony likely to be critical in determining the outcome of the trial. For the Guardian, detailed and prominent reporting of, and commentary on, the Assange extradition hearings should be a double priority.

So how to explain the Guardian’s silence?

The book by Leigh and Harding, WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy, made a lot of money for the Guardian and its authors by hurriedly cashing in on the early notoriety around Assange and Wikileaks. But the problem today is that the Guardian has precisely no interest in drawing attention to the book outside the confines of a repressive courtroom. Indeed, were the book to be subjected to any serious scrutiny, it might now look like an embarrassing, journalistic fraud.

The two authors used the book not only to vent their personal animosity towards Assange – in part because he refused to let them write his official biography – but also to divulge a complex password entrusted to Leigh by Assange that provided access to an online cache of encrypted documents. That egregious mistake by the Guardian opened the door for every security service in the world to break into the file, as well as other files once they could crack Assange’s sophisticated formula for devising passwords.

Much of the furore about Assange’s supposed failure to protect names in the leaked documents published by Assange – now at the heart of the extradition case – stems from Leigh’s much-obscured role in sabotaging Wikileaks’ work. Assange was forced into a damage limitation operation because of Leigh’s incompetence, forcing him to hurriedly publish files so that anyone worried they had been named in the documents could know before hostile security services identified them.

Computer expert at Assange hearing calls the Guardian’s David Leigh ‘a bad faith actor’ over his publishing a Wikileaks password that opened the door to every security service in the world being able to access 250,000 encrypted cables https://t.co/QLJj1McNrJ

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 22, 2020

This week at the Assange hearings, Professor Christian Grothoff, a computer expert at Bern University, noted that Leigh had recounted in his 2011 book how he pressured a reluctant Assange into giving him the password. In his testimony, Grothoff referred to Leigh as a “bad faith actor”.

‘Not a reliable source’

Nearly a decade ago Leigh and Harding could not have imagined what would be at stake all these years later – for Assange and for other journalists – because of an accusation in their book that the Wikileaks founder recklessly failed to redact names before publishing the Afghan and Iraq war diaries.

The basis of the accusation rests on Leigh’s highly contentious recollection of a discussion with three other journalists and Assange at a restaurant near the Guardian’s former offices in July 2010, shortly before publication of the Afghan revelations.

According to Leigh, during a conversation about the risks of publication to those who had worked with the US, Assange said: “They’re informants, they deserve to die.” Lawyers for the US have repeatedly cited this line as proof that Assange was indifferent to the fate of those identified in the documents and so did not expend care in redacting names. (Let us note, as an aside, that the US has failed to show that anyone was actually put in harm’s way from publication, and in the Manning trial a US official admitted that no one had been harmed.)

The problem is that Leigh’s recollection of the dinner has not been confirmed by anyone else, and is hotly disputed by another participant, John Goetz of Der Spiegel. He has sworn an affidavit saying Leigh is wrong. He gave testimony at the Old Bailey for the defence last week. Extraordinarily the judge, Vanessa Baraitser, refused to allow him to contest Leigh’s claim, even though lawyers for the US have repeatedly cited that claim.

Statement from journalist John Goetz of Der Spiegel attesting that Assange never made the “they deserve it” comment he was accused of saying by The Guardian’s David Leigh. Goetz was at the dinner Assange is alleged to have said it. https://t.co/wexkKhwKg7 pic.twitter.com/FdFRAG4oNH

— Caitlin Johnstone ⏳ (@caitoz) September 8, 2020

Further, Goetz, as well as Nicky Hager, an investigative journalist from New Zealand, and Professor John Sloboda, of Iraq Body Count, all of whom worked with Wikileaks to redact names at different times, have testified that Assange was meticulous about the redaction process. Goetz admitted that he had been personally exasperated by the delays imposed by Assange to carry out redactions:

At that time, I remember being very, very irritated by the constant, unending reminders by Assange that we needed to be secure, that we needed to encrypt things, that we needed to use encrypted chats. … The amount of precautions around the safety of the material were enormous. I thought it was paranoid and crazy but it later became standard journalistic practice.

Prof Sloboda noted that, as Goetz had implied in his testimony, the pressure to cut corners on redaction came not from Assange but from Wikileaks’ “media partners”, who were desperate to get on with publication. One of the most prominent of those partners, of course, was the Guardian. According to the account of proceedings at the Old Bailey by former UK ambassador Craig Murray:

Goetz [of Der Spiegel] recalled an email from David Leigh of The Guardian stating that publication of some stories was delayed because of the amount of time WikiLeaks were devoting to the redaction process to get rid of the “bad stuff.”

When confronted by US counsel with Leigh’s claim in the book about the restaurant conversation, Hager observed witheringly: “I would not regard that [Leigh and Harding’s book] as a reliable source.” Under oath, he ascribed Leigh’s account of the events of that time to “animosity”.

Scoop exposed as fabrication

Harding is hardly a dispassionate observer either. His most recent “scoop” on Assange, published in the Guardian two years ago, has been exposed as an entirely fabricated smear. It claimed that Assange secretly met a Trump aide, Paul Manafort, and unnamed “Russians” while he was confined to the Ecuadorian embassy in 2016.

Harding’s transparent aim in making this false claim was to revive a so-called “Russiagate” smear suggesting that, in the run-up to the 2016 US presidential election, Assange conspired with the Trump camp and Russian president Vladimir Putin to help get Trump elected. These allegations proved pivotal in alienating Democrats who might otherwise have rallied to Assange’s side, and have helped forge bipartisan support for Trump’s current efforts to extradite Assange and jail him.

The now forgotten context for these claims was Wikileaks’ publication shortly before the election of a stash of internal Democratic party emails. They exposed corruption, including efforts by Democratic officials to sabotage the party’s primaries to undermine Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton’s rival for the party’s presidential nomination.

Those closest to the release of the emails have maintained that they were leaked by a Democratic party insider. But the Democratic leadership had a pressing need to deflect attention from what the emails revealed. Instead they actively sought to warm up a Cold War-style narrative that the emails had been hacked by Russia to foil the US democratic process and get Trump into power.

No evidence was ever produced for this allegation. Harding, however, was one of the leading proponents of the Russiagate narrative, producing another of his famously fast turnaround books on the subject, Collusion. The complete absence of any supporting evidence for Harding’s claims was exposed in dramatic fashion when he was questioned by journalist Aaron Mate.

Harding’s 2018 story about Manafort was meant to add another layer of confusing mischief to an already tawdry smear campaign. But problematically for Harding, the Ecuadorian embassy at the time of Manafort’s supposed visit was probably the most heavily surveilled building in London. The CIA, as we would later learn, had even illegally installed cameras inside Assange’s quarters to spy on him. There was no way that Manafort and various “Russians” could have visited Assange without leaving a trail of video evidence. And yet none exists. Rather than retract the story, the Guardian has gone to ground, simply refusing to engage with critics.

Most likely, either Harding or a source were fed the story by a security service in a further bid to damage Assange. Harding made not even the most cursory checks to ensure that his “exclusive” was true.

Unwilling to speak in court

Despite both Leigh and Harding’s dismal track record in their dealings with Assange, one might imagine that at this critical point – as Assange faces extradition and jail for doing journalism – the pair would want to have their voices heard directly in court rather than allow lawyers to speak for them or allow other journalists to suggest unchallenged that they are “unreliable” or “bad faith” actors.

Leigh could testify at the Old Bailey that he stands by his claims that Assange was indifferent to the dangers posed to informants; or he could concede that his recollection of events may have been mistaken; or clarify that, whatever Assange said at the infamous dinner, he did in fact work scrupulously to redact names – as other witnesses have testified.

Given the grave stakes, for Assange and for journalism, that would be the only honourable thing for Leigh to do: to give his testimony and submit to cross-examination. Instead he shelters behind the US counsel’s interpretation of his words and Judge Baraitser’s refusal to allow anyone else to challenge it, as though Leigh brought his claim down from the mountain top.

The Guardian too, given it central role in the Assange saga, might have been expected to insist on appearing in court, or at the very least to be publishing editorials furiously defending Assange from the concerted legal assault on his rights and journalism’s future. The Guardian’s “star” leftwing columnists, figures like George Monbiot and Owen Jones, might similarly be expected to be rallying readers’ concerns, both in the paper’s pages and on their own social media accounts. Instead they have barely raised their voices above a whisper, as though fearful for their jobs.

These failings are not about the behaviour of any single journalist. They reflect a culture at the Guardian, and by extension in the wider corporate media, that abhors the kind of journalism Assange promoted: a journalism that is open, genuinely truth-seeking, non-aligned and collaborative rather than competitive. The Guardian wants journalism as a closed club, one where journalists are once again treated as high priests by their flock of readers, who know only what the corporate media is willing to disclose to them.

Assange understood the problem back in 2011, as he explained in his interview with Mark Davis (38.00mins):

There is a point I want to make about perceived moral institutions, such as the Guardian and New York Times. The Guardian has good people in it. It also has a coterie of people at the top who have other interests. … What drives a paper like the Guardian or New York Times is not their inner moral values. It is simply that they have a market. In the UK, there is a market called “educated liberals”. Educated liberals want to buy a newspaper like the Guardian and therefore an institution arises to fulfil that market. … What is in the newspaper is not a reflection of the values of the people in that institution, it is a reflection of the market demand.

That market demand, in turn, is shaped not by moral values but by economic forces – forces that need a media elite, just as they do a political elite, to shore up an ideological worldview that keeps those elites in power. Assange threatened to bring that whole edifice crashing down. That is why the institutions of the Guardian and the New York Times will shed no more tears than Donald Trump and Joe Biden if Assange ends up spending the rest of his life behind bars.

There is a scandal and a crisis in British journalism. For the past three weeks or so a crucial extradition hearing has been taking place in the Central Criminal Court in London. You won’t know about it if you rely for your news on the established newspapers, the BBC or ITV or Channel 4.

The case revolves around Julian Assange, of Wikileaks; and the government of the United States of America, which wishes to extradite this pioneering journalist and revealer of the truth and put him into a horrible prison until he dies.

Apparently there are about ten journalists regularly attending the court and taking notes, but as far as we know only one of them is publishing serious accounts of the ridiculous and disgraceful procedures. The vast majority of the public are unaware the proceedings are even taking place.

This is a case about free speech, exposure of wicked secrets, and the ability of journalists to operate in society. Yet journalists themselves are turning their backs on it. It almost seems as if they hope Assange will be taken away, removed from public view.

The only journalist who is doing this is Craig Murray, formerly the UK Ambassador to Uzbekistan, whose blog probably has a small readership, and who himself is in jeopardy of prison because of his fearless exposure of establishment corruption and lying. http://www.craigmurray.org.uk

The Assange “trial” is comparable to that of Dreyfus, with our “free” press betraying both the word itself and their readers and viewers. Our judiciary is being corrupted and our judicial system poisoned at the behest of Trump and as a result we are sliding towards fascism.

We are both retired. Jacob was a journalist and union leader on the pre-Murdoch Times for 20 years and then the deputy general secretary of the National Union of Journalists from 1980 to 1997. Bernie was a senior journalist on the Birmingham Post, Guardian and Independent, then editor of the NUJ newspaper “Journalist”, then an organiser, negotiator and case worker for the NUJ, then general secretary of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain from 2000 to 2016.

Jacob Ecclestone

Bernie Corbett

Thank you Jonathan. Excellent article as always. I just want to add that I believe some of the astonishing lack of support for Assange is due to the false rape allegation. In my experience, there is a substantial part of the left who still do not understand that the false rape allegation muddied the waters from the start. I read a plausible explanation from Assange himself a long time ago but now cannot find it. But a crucial part of the explanation involves an understanding of Swedish law, that counts the non-wearing of a condom as rape. Here is an account of these events, ironically from the Guardian nine years ago,

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2010/dec/17/julian-assange-sweden

As someone with a close relative raped at gunpoint by two men nearly fifty years ago, I am hardly likely to minimise rape. Many people still cling to the argument that “there is no smoke without fire”, and I think it is worth pointing out, that , for all the marvellous detail in Jonathan’s article, the sad fact remains that the rape allegation may be what prevents otherwise decent people from seeing that Assange is innocent of all charges.

What I particularly enjoyed about his piece was Cook’s searing indictment of the spinelessness of The Guardian and its alleged journalists, Luke Harding and David Leigh, with regard to the Assange affaire. The real clincher is Aaron Maté’s gimlet-eyed demolition job of a smirking and condescending Harding on the Real News Channel in 2017. From the start Harding can see he’s in danger of being skewered by Maté’s simple – but polite – requests for some PROOF of the Putin/Assange/Trump link and risibly tries every trick in the book to get himself off the hook, distract and change the subject, until he finally loses his rag in the last few minutes – and cuts the video link. It’s a must-watch. Of course, since then, Both Maté and Max Blumenthal on Real News and Push Back have comprehensively demolished the whole ‘Russiagate’ hoax, without having to bother themselves any further with Harding’s threadbare stenography. Cook and Maté are the real journalists. Thank God there are still some left.

Susan, Yes, there is absolutely no doubt whatsoever that Julian was set up…… I mean for a start, one of the women – the one that invited him over to Sweden to give a speech AND offered him her apartment to stay at (whilst she went away to visit her parents for a few days) – sent a text to a friend the day after it allegedly happened, telling the friend that she was at a party with some of the best people on the planet (including Julian), or words to that effect.

Right, I knew that Craig Murray had covered the tweet in one of his many, many articles in relation to the plight of Julian, and I just went on to his blog and did a search (re ‘julian assange’) and found it. So here’s a link to the article, and what she actually says in her tweet is: ‘Sitting outdoors at 02:00 and hardly freezing with the world’s coolest smartest people, it’s amazing! #fb’, and she tweets this to a friend AFTER (the day after I think) the alleged sexual assault happened:

Why I am Convinced that Anna Ardin is a Liar

https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2012/09/why-i-am-convinced-that-anna-ardin-is-a-liar/

As I say, there are numerous articles on his blog that Craig has written over the years in relation to Julian, along with Julian’s full defence statement to the Swedish prosecutor. Craig’s search engine is down the page a bit on the right-hand side, and if you type in >julian assange< it will bring up all the related articles, albeit in full. So given that Craig has written extensively about the ongoing extradition hearing, you'll need to do a 'rapid' scroll to get down to the other articles, otherwise it will take forever!

PS Now I have absolutely no idea about Julian’s love-life, but I’d be very surprised if he didn’t have more than a few liaisons over the years AND prior to his trip to Sweden, and yet I have never-EVER heard of any woman claiming that Julian sexually assaulted her, and yet – in the space of a few days after going to Sweden……. Hmm!

Oh, right, and then there’s the ‘ripped condom’ which doesn’t have a trace of Julian’s DNA on it! But this apparently didn’t have any significance whatsoever as far as the prosecutor was concerned!

PS Now, needless to say, IF it had been just one woman (in Sweden) who had made a claim of sexual assault against Julian, well, it would have just been HIS word against hers, but if there were TWO women making such claims, well then, there’s absolutely no doubt about it, is there, Julian MUST be guilty! And these are two women that supposedly didn’t know each-other prior to the event where Julian gave his talk, but then suddenly became aquainted and, as such, the woman who had initially slept with Julian accompanies the OTHER woman to a police station when SHE wants to ascertain if someone – ie Julian – can be made to have a test because she was concerned about the possibility of having contracted HIV.

Now I don’t recall what Julian said in relation to this in his defence statement, if anything, but it seems HIGHLY unlikely to me that Julian would refuse to have a test if the woman in question was very concerned about having contracted HIV (and yet the other woman, who claimed that Julian ripped the condom, WASN’T!), but why would you think to actually go to a police station anyway, and not just phone and make a general inquiry as to whether someone can be made to take a test in such circumstances OR phone a clinic and inquire. OR check on the internet!

I could say much about the whole episode, but how very fortuitous for the PTB that it all played out the way it did, and ALSO that the second woman should just happen to text someone saying that she “did not want to put any charges on Julian Assange” but that “the police were keen on getting their hands on him”.

Was it a Blind, as they call it in the trade? I have little doubt that it WAS, and for the obvious reason! As I say, it ALL seems Oh-SO pat!

It wouldn’t surprise me if, had the two journalists gunned down by that US helicopter in Iraq, been not Reuters employees, but Guardian ones, that that ghastly example of the Fourth Estate would still be quite happy to allow Julian Assange to , “ Take the Rap“, with scarcely a mention in any of its evil pages of why the US government is anxious to bang him up for 175 years.

“The real clincher is Aaron Maté’s gimlet-eyed demolition job of a smirking and condescending Harding on the Real News Channel in 2017. From the start Harding can see he’s in danger of being skewered by Maté’s simple – but polite – requests for some PROOF of the Putin/Assange/Trump link and risibly tries every trick in the book to get himself off the hook, distract and change the subject, until he finally loses his rag in the last few minutes – and cuts the video link. It’s a must-watch” – Steve Tiller (above).

This seems to refer to:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Ikf1uZli4g

There is some reason to believe that Luke Harding works for British intelligence:

https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Luke_Harding

I remember reading an account by Julian of his visit to Sweden which makes clear that he was unwittingly ‘set up’ for an allegation of rape.

Trump strikes me as a bit of an empty vessel who seemed to flip flop on this topic. I’d be interested to know who encouraged him to pursue Assange for espionage. Are they still at work here? Its nothing less than a straightforward attack on journalism as a whole and I say whoever they are they need to be called out. Forgive my ignorance if this is old news.