Reinventing Passover (Pesach) – some thoughts

JVL Introduction

Here is a compilation, a reflection on the way the passover holiday and celebration has been redefined in recent times as a narrative of liberation and solidarity with the oppressed.

It was not always so.

We discuss some recent contributions on the emergence of alterative seders, the ongoing debate about the Jewish values enshrined in the story, the role of Israel in Jewish life in the diaspora and much else besides, including on why Jewish Millennials are flocking to socialism, Jermy Corbyn in conversation with Tania about the meaning of passover, and Ira Glunt’s personal seder, a rebellion against all he finds offensive in the traditional narrative. This year we also have the Jewdas Haggadah, previously highlighted on this webpage.

And all about an event which, as Ariel David reminds us, never took place!

Reinventing Passover (Pesach) – a compilation

From our passover correspondent

23 April 2019

The passover story, based on the biblical book of Exodus, celebrate the deliverance of the Jews from Egypt, from oppression by the Pharaoh. It centres round the seder, a family meal at which a specific set of tasks must be completed and rituals covered in a specific order. (The word ‘seder’ means ‘order’.) This order is set out in a book called the Haggadah.

The orthodox Jewish tradition is clear. Passover is a celebration of deliverance – but a deliverance at the hand of God alone. The people of Israel were only involved passively. Human agency was not involved.

Ever since the Jewish enlightenment, strands of Judaism have rebelled against that interpretation of the Torah and notions of rebellion against injustice and self-liberation have been brought in. The idea of solidarity, of welcoming the stranger, emphasises particularly the notion that Jews had been strangers in Egypt.

The idea of alternative seders came into its own in the sixties and, as part of the civil rights movement in the States. The organiser of the first Freedom Seder was Arthur Waskow, an American political activist, author and rabbi associated with the Jewish Renewal movement.

As Waskow recalled in 2005, the First Freedom seder was “held on the third night of Passover, 4th April 1969, the first anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King, in the basement of a Black church in Washington DC. About 800 people took part, half of them Jews, the rest Black and white Christians.”

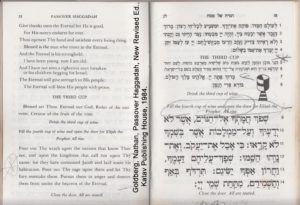

A contributing editor to the radical magazine Ramparts, Waskow produced the first Freedom Haggadah (image above) of which he said in the preface:

For us this Haggadah is deeply Jewish, but not only Jewish. In our world all men face the Pharaohs who could exterminate them any moment, and so enslave them all the time. Passover therefore fuses, for an instant, with the history and the future of all mankind. But it fuses for an instant, and in the fusion it does not disappear. The particularly Jewish lives within the universally human, at the same time that the universally human lives within the particularly Jewish.

Waskow also recalled later that

“It seems to have been the first Haggadah, certainly the first widely circulated, that celebrated the liberation of other peoples as well as the liberation of the Jewish people.”

“The Freedom Seder was welcomed by tens of thousands of Jews, and soon became the model and stimulus for many Haggadot that made the Passover Seder an affirmation of the liberation of its celebrants — feminist Haggadot, environmentalist Haggadot, antiwar Haggadot, vegetarian Haggadot, pro-labor Haggadot.”

“More broadly, it also helped point the way for a renewal of Jewish liturgy and celebration, the fusion of liturgy with social action, and the upwelling of a movement for Jewish renewal from the “grass roots” of the Jewish people.”

The Freedom Haggadah can be downloaded here.

**********

As Waskow pointed out, other liberatory and solidarity seders followed, most notably the first women-only Passover seder in 1976.

It was held in Esther M. Broner’s New York City apartment and led by her, with 13 women attending, including Gloria Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, and Phyllis Chesler. As the Wikipedia entry on Esther Broner records: “In the spring of 1976 Broner published this ‘Women’s Haggadah’ in Ms. magazine, later publishing it as a book in 1994; this haggadah is meant to include women where only men had been mentioned in traditional haggadahs, and it features the Wise Women, the Four Daughters, the Women’s Questions, the Women’s Plagues, and a women-centric ‘Dayenu’.

Clarrie Feinstein’s recent account of Women’s Seders: the vehicle for Jewish feminist liberation is reproduced below

**********

The anti apartheid movement, too, saw seders its own seders. As Howard Sackstein recalled:

In 1985, Jews for Social Justice (JSJ), the South African Jewish anti-apartheid movement, decided that the story of Passover, the historical exodus from slavery to freedom, held a universal message for all of those in the anti-apartheid struggle.

Determined to inspire hope and share the message of freedom with others, JSJ decided to host a series of Freedom Seders with the leadership of the anti-apartheid movement to celebrate the universal message of liberation.

I approached Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris with the idea, and he immediately committed himself to support and attend the seder. He also committed himself to designing a universal Haggadah that would not only share the story of Passover, but also Jewish teachings on freedom. The Haggadah would include universal writings on liberty from Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi, and other icons of liberation.

Maxine Hart and I undertook to get as many activists involved in the proceedings. We invited, among others, the leadership of the United Democratic Front (the UDF was the internal wing of the ANC); the trade union movement, including Cosatu (Congress of South African Trade Unions); the End Conscription Campaign; the National Union of South African Students; the Five Freedoms Forum; the Detainees Parents Support Committee; the Black Sash; the Johannesburg Democratic Action Committee; the South African Council of Churches; and the National Educational Crisis Committee. The response from anti-apartheid activists was overwhelming.

As usual, the attempt to cajole the leadership of the South African Jewish community into attending was left to me. Their response was significantly more mooted [sic] than that of the political activists…

Read more at Freedom Seders – from revolution to revelation

Does Palestine make celebrating the Jewish Passover impossible?

Robert Cohen, Patheos

19th April 2019

Tonight (Friday 19th April) I’ll be celebrating the Jewish festival of Passover with my family. We’ll do it in our own way, using our own home-curated Haggadah which draws on some radical and contemporary Jewish thought to tell the story of the Exodus from Egypt and give it modern meaning and relevance.

The traditional Passover service commands us to think as if we ourselves had left ancient Egypt. We are right there witnessing the ten plagues. We are personally liberated by the Almighty who rescues us with a ‘strong hand and an outstretched arm’. We march with Moses across the parted Red Sea (our feet kept dry) and on towards Mt. Sinai to receive the Law. It’s all a beautiful and captivating religious myth which is deeply ingrained for anyone who’s experienced a Jewish upbringing.

But for a growing number of Jews around the world our relationship to the Palestinian people has become the greatest challenge to our Jewish identity and values. How can we celebrate our ‘feast of freedom’ and tell the story of our Exodus from the ‘narrow place’ of ‘Mitzryim’ while we deny, or stay silent, about the oppression of Palestine? It’s a profound challenge to our faith and the understanding of our own history.

Attempting to uphold a Jewish ideal of justice and freedom is not easy when you’ve just read that Israel has detained, kidnapped or jailed 1,000,000 Palestinians since 1948.

Compromised

Even the most progressive of Jewish charities find themselves compromised at Passover by the denial that surrounds the mainstream Jewish understanding of Israel/Palestine.

I’ve been collecting Haggadot for more than 20 years, especially alternative and radical re-interpretations of the traditional liturgy. This year I bought a copy of the HIAS Haggadah.

HIAS is an American Jewish charity which works with refugees and asylum seekers coming to the United States. It was established in 1881 as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society to assist Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe. You may recall that the murderous attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh last year was targeted by a white supremacist because of its support for HIAS.

Reading through the HIAS Haggadah you can see the tremendous work it’s doing. It uses stories from Syria, Somalia, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Congo, and many other troubled places to bring to life the modern meaning of oppression and liberty and the contribution that refugees have made to American society. The liturgy several times refers to the 68 million displaced people and refugees in the world today. But nowhere does it speak of the 5.4 million Palestinian refugees included in that number. Why not? What makes it so difficult to include their story amongst all the others that are told?

Revenge fantasies

The traditional Haggadah service book, which most Jewish families still use today, was compiled many hundreds of years ago and written from the perspective of a community that was already long-suffering. It records our annual longing for the Prophet Elijah to return and herald our redemption from oppression once again. It even recounts an argument between famous ancient rabbis who believed that far more than ten plagues were sent to smite the Egyptians. Rabbi Akiva insists, by interpreting the words of the Torah with exceptional creativity, that it was in fact 50 plagues that struck in Egypt and a further 250 unleashed against Pharaoh’s army at the Red Sea.

It’s a kind of revenge fantasy only appropriate to a people without power and still oppressed. Today we are in a very different place. Today, we have become Pharaoh to another people.

#NoPassoverZone

My friend and teacher Professor Marc Ellis, has declared this year a #NoPassover zone in his home in Florida. It’s an understandable position to take. Our recent history seems to have fatally compromised the very foundations of our faith. Is there a way back? Is there a way forward? Or will Jews in opposition to Zionism have to find an entirely new way to express their Jewish identity?So does Palestine make celebrating the Jewish Passover impossible?

Yes and no.

It certainly makes it a lot harder. It demands you place yourself not only in the story of the Hebrews’ redemption but in the oppression caused today in the name of Jewish security and Jewish safety.

In truth we can never experience Palestinian suffering. Our attempt to even imagine what it is like is at risk from shallowness and tokenism. We are left with symbolic gestures like placing Palestinian olive oil on our seder plate alongside the traditional Passover symbols of bitter herbs and unleavened bread. But it’s better than celebrating Passover in a fog of denial.

For this year’s service, I’ve brought back and revised a poem I wrote five years ago. It feels appropriate to dedicate it to Marc Ellis.

A poem: ‘On the Impossibility of Passover’

On my journey to the Promised Land

My feet have become entangled

In the roots of upturned olive trees

I see homes turned to rubble

By a clenched fist and an outstretched arm

Blocking the path to righteousness

On this night, deliverance is held up at the checkpoint

And freedom is cut down by snipers

So what is there left to celebrate

With timbrels and dancing?

I ask my questions

Eat bitter herbs

And recount the plagues that we have sent

Exiled

Scattered

Occupied

Besieged

Humiliated

Arrested

Imprisoned

Teargassed

Crippled

Martyred

We have melted our inheritance

and cast ourselves a new golden calf to worship

And the words from Sinai

Are crushed beneath its hooves

There is no Moses to climb the mountain a third time

Elijah is detained indefinitely

The mission is lost

And the angels gather to weep

It is the first night of the Feast of Freedom

I open the Haggadah

Place olives on the Seder plate

And confront the impossibility of Passover

This year in Mitzryim

This year in the narrow place

Radical reappraisal

Celebrating Passover needs a radical reappraisal – but that’s just the beginning. How we see our Jewish selves, our relationship to Israel and the global Jewish community, and how we link our historical experience to others, and in particular the people of Palestine, is the real challenge.

Tonight, we’ll conclude our family meal with this passage written by Aurora Levins Morales, a poet and activist. I discovered her writing in the 2018 Jewish Voice for Peace Haggadah

“This time we cannot cross until we carry each other. All of us refugees, all of us prophets. No more taking turns on history’s wheel, trying to collect old debts no one can pay. The sea will not open that way. This time that country is what we promise each other, our rage pressed cheek to cheek until tears flood the space between, until there are no enemies left, because this time no one will be left to drown and all of us must be chosen. This time it’s all of us or none.”

So if you’re celebrating Passover, handle it with care and deep reflection. And if you’re deliberating choosing not to celebrate, then I understand completely.

Why Are Jewish Millennials Flocking To Socialism? Passover Has The Answer

Every year at the Passover seder, I make a point of recounting a midrash I once read about the Haggadah’s Four Children casting each child as a different generation of American Jewry. The wise child is the pious immigrant. The wicked child is the assimilated rebel who refuses their parents’ foreign language and customs. The simple child is the offspring of the wicked generation, those Jews who were never taught Yiddish or Talmud. And finally, there’s the child who doesn’t know how to ask.

For a while this seemed like a good description of my generation of American Jewish millennials, so far removed from Jewish identity that we don’t even seek it, don’t even ask to learn about it.

But in recent years, with the emergence of some of the deepest fissures in our communities, this cute metaphor has changed. We young Jews — the most assimilated in American Jewish history — have learned how to ask.

We’re not just asking about religious traditions. We’re asking the more existential questions of being Jewish, like why has American Judaism become this pastiche of light spirituality and fervent Zionism? What does being Jewish in 21st Century America really mean? What are the Jewish values that have been lost since our ancestors arrived on these shores, and are there some that it may be worth resuscitating?

And we won’t stop asking until we get some good answers.

Surveying the young American Jewish landscape today, this phenomenon of questioning is immediately apparent with regards to Israel. From the Open Hillel movement to the anti-Occupation group IfNotNow, young Jews are increasingly questioning the no-daylight closeness that institutional American Judaism has maintained towards Israel for decades. One of IfNotNow’s signature initiatives is the You Never Told Me campaign, in which young alumni of Jewish summer camps, day schools, and youth groups demand our alma maters start to teach us about and answer for the Occupation.

This isn’t surprising. We’re a generation too young to remember the Oslo Accords’ hope for peace. We came of age at a time when Israel invaded and blockaded Gaza, acting with increasing impunity in building West Bank settlements. When the Prime Minister of Israel garners heaps of praise from anti-Semites around the world, and courts an American government indifferent to white supremacy, it’s hard not to question Israel’s place in American Jewish identity.

But it’s not just about Israel and Zionism. A spirit of questioning the established systems of power flows throw much wider trends in millennial Jewry, which has flocked to radical groups both officially Jewish and not. At meetings of the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, I’m rarely the only Aaron in the room.

Of course, young Americans as a whole are embracing the political spirit of questioning. More of us prefer socialism than capitalism. We all came of age in the shadow of the “War on Terror,” the Great Recession, and Donald Trump’s election, upending much of the conventional wisdom around politics, the economy, and society more generally. When everything you’re taught about how the world is supposed to work is clearly not true, the only option is the radical project of questioning, of demanding better answers for why things are how they are, and what we must do to make them better.

But for American Jews there is more to it than that. Our trend of assimilation in the 20th Century has dovetailed with rising prosperity, both for America at large and for Jews specifically. As we reaped the material and social benefits of postwar America, including the fall of most institutional anti-Semitism, it was easy to embrace the vision of an exceptionalist America whose tide of liberal capitalism lifted all boats. The distinctly Jewish identities that our forbearers brought with them from the Old Country slipped off into an ever more distant past.

Yet with the great upheaval of the past decade, including a recent surge in anti-Semitic attacks, America’s siren song to the Jews has played out.

As we crash into the rocks, we young Jews are looking back to the Jewish identity that sustained and empowered our ancestors to once again do so for us.

This hasn’t meant a return to religion, necessarily, but to the great anti-capitalist, radical Judaism of early 20th century immigrants. Of course this generation was hardly monolithic. As communists, socialists, and anarchists, they fought intensely among themselves, divided by their attitudes on assimilation, Zionism, and fealty to the Soviet Union.

But what the Jewish radicals of yore shared was a commitment to questioning the capitalist society they lived in, even when it meant arrest and even deportation.

To question is not easy, but to live an honest life in dishonest times, it is necessary.

This heritage is personal for me. For the ancestor in my own family who I look back to as embodying the “wise child” was not Orthodox but a radical: my great-grandfather Samuel. A raincoat factory worker, Samuel was active in the leftist scene of 1910’s New York, editing a Yiddish anarchist newspaper. He and my great-grandmother Rose even raised their children in the radical Ferrer Colony in rural Stelton, New Jersey, whose progressive Modern School encouraged my grandfather’s self-starter interest in machinery at a young age. His sister, my great-aunt Clara, would remain a committed anarchist her whole life, even hitchhiking to Canada to visit Emma Goldman in exile.

Jewish radicalism runs in my family. But even stronger for me and many of my fellow millennial Jews is a powerful tradition that runs not only separate from but contrary to the American capitalist mainstream that has been so thoroughly discredited.

It gives us a community we can be part of without excluding others based on race, religion, or nationality. It is a way to be Jewish without compromising our values by mixing them with America’s capitalism, Orthodoxy’s piety, or Zionism’s nationalism.

In short, it is a Judaism urgently needed in this moment.

At my seder this year, I will still tell the generational parable of the Four Children. But I will also encourage us all to be a Fifth Child, the Child Who’s Learned How to Ask. To ask about Emma Goldman. To ask about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. To ask about the Occupation. To ask about big business’s role in climate change.

In asking, we not only learn, but also challenge. In asking, we embrace the best of Judaism.

Aaron Freedman is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY. Follow him at @freedaaron

Women’s Seders: the vehicle for Jewish feminist liberation

Clarrie Feinstein, Canadian Jewish News

18 April 2019

In 1976, Jewish feminists came together to celebrate a third night of Passover – a women’s only celebration — The Women’s Seder. It was hosted for the first time in the creator’s home, feminist and academic, E.M. Broner, who wanted to commemorate the female history that is often ignored in the story of Exodus. The Women’s Haggadah, co-written by Broner and Nomi Nimrod redefined the seder to focus on the female narrative. As Broner stated, “we wanted to take a major Jewish holiday, to continue interpreting it, to insert ourselves into it, to make ourselves historic.”

The direct correlation between female oppression in modern day society and Jewish oppression seen in the story of Passover, lead Jewish feminists to identify strongly with this specific narrative of oppression.

The central female figures in the story like, Shifra, Puah, Yocheved and Miriam are hardly given a voice, yet their defiance and strong will needed to be celebrated and recognized. The women’s seder centralized the biblical female figures, providing rituals to commemorate the strength of women at the seder table. By doing this, a space was created for women to come forward with their personal experiences of oppression as they found solace with the story of Exodus.

The four children become the four daughters, with the wise child becoming the chachama, meaning both “wise woman” and “midwife.” The word midwife evokes the story of the midwives Shifra and Puah who disobeyed the king of Egypt by not killing the male firstborns of the Hebrews. By defying his orders, it allowed the Hebrews to, “multiply and increase greatly.”

The lessons of Shifra and Puah can be shared with the wise daughter. As scholar Leora Eisenstadt said, the daughter is taught that, “questions are at the heart of movements for freedom, that questioning the powerful is the first seed of liberation.” This resonated with women, especially during Second Wave Feminism when many inequalities were present in both religious and secular, social and private spheres.

Another woman that is commemorated is Moses’ mother, Yocheved. She hides her son for three months and builds him a tevah – a protective ark – to float him on the Nile. The tevah is only seen one other time in the text during the story of Noah, becoming “the vehicle of salvation in waters of destruction.” Yocheved embodies the protective and nurturing maternal perspective, which is omitted from the seder rituals. However, her role in the story personifies female strength, which saves Moses, the savior of the Jewish people.

The most important female figure in the story of Exodus is the prophet Miriam, who is not mentioned in the traditional haggadah. Miriam’s cup has become a commonplace ritual, that is not only present in women’s seders, but also in traditional seders. Her cup stands besides Elijah’s cup, as Miriam’s importance to the Israelites cannot be ignored.

The cup represents Miriam’s well, which is said to contain healing and sustaining waters. It followed Miriam for the 40 years of wandering in the desert and was credited to her merit as an individual. Symbolically, Jewish feminists interpreted the water as the substance that sustains all people through their journeys. The cup honours Miriam, highlighting her role in the Exodus story.

There is also the option of including a tambourine, which is used by Miriam and the Israelite women when they danced and sang on the shores of the Red Sea, as stated in the book of Exodus, “And Miriam the prophetess, took the timbrel in her hand and all the women went out after her with timbrels dancing.” What is interesting to note, is Miriam’s song is inclusive of all “shiru adonai” (Sing to the Lord) using a plural form of the verb to invite the entire community to sing, where Moses uses the singular “ashira l’adonai” (I will sing to the Lord). Miriam brings the entire Jewish community together into her celebration with the timbrels. This inclusivity is a major tenant in women’s seders, which brought together the marginalized to celebrate together in a space where they have often been excluded.

Women also lead their own rituals, reclaiming their role in Passover. Often, women were responsible for preparing and planning the Passover meal, readying the home for the holiday, which would take days of preparation. Yet their role in the seder was marginal. The Jewish feminist movement found this subservience problematic, especially on a holiday that discussed Jewish liberation.

The hypocrisy of Passover for women is exemplified in this Talmudic statement, “A women at her husband’s is not required to recline, and if she is an important woman, she is required to recline.” The first part of the statement says that the man is at the centre of the seder table, meaning a woman is not free in the eyes of God or in the eyes of Jews present. She is required to be present during the commemoration of her peoples’ liberation, yet she is also subservient to her husband. As feminist Leah Shakdiel wrote in, We Can’t be Free Until all Women are Important, “we are free as Jews, but not free as women.” The second part of the statement says “important woman” singling out certain women, instead of stating that “all” women are important.

Herein lies the struggle so many women identify with in the story of Passover: women’s subservience, which permeates into the Passover rituals and the perspective the traditional seders adopt. In order to address the issues that have been presented, women wanted to reclaim their place at the seder table through the creation of a new ritual: the women’s seder. Women no longer wanted to be invisible in Jewish culture. They wanted to recognize the female biblical figures incorporating them into their holiday rituals, forming new Jewish traditions, which should have always been in practice.

Another ritual that has been incorporated to allow for inclusivity is the orange. While the origin is unclear, it is speculated that a heckler stated to a Jewish feminist, “being a Jewish lesbian is like eating bread on Passover.” In response to this, early lesbian feminists haggadot proposed including a crust of bread on the seder plate, but then changed it to an orange to be less subversive, representing “transformation, not transgression.” The symbolic meaning of the orange is then interpreted to signify that something that is deemed as “other” has a place in Jewish tradition. When the orange segments are shared, it represents the “fruitfulness in our societies created by the diversity of our sexualities.”

These new traditions allow for both a female centric role in the story of Exodus but also for inclusive environments, which have often excluded female participation. In the context of the 1970s “women-only” groups were vital, as very few opportunities were afforded to women to take on leadership or participatory roles even in liberal forms of Judaism. Women were often in the “background” but never fully central.

These specific seders allowed women to sit and serve themselves, giving them the opportunity to become teachers and leaders in the service. Historically, in Judaism and the secular world, education was often denied to women, silencing their voice. In this setting women can reclaim their Jewish voice, allowing them the opportunity to share experiences and pose questions that might otherwise be considered “distractions” at traditional seders.

Because of this, the women’s seder became the catalyst for Jewish self-expression and liberation.

Jeremy Corbyn in conversation with a young Jewish Labour member

I had the pleasure of sitting down with Tania, a young Jewish Labour member, to discuss the meaning of Passover. I wish Jewish communities in Britain and across the world Chag Sameach.

The Pharaoh Ahmose I fighting the Hyksos Wikimedia

For You Were (Not) Slaves in Egypt: The Ancient Memories Behind the Exodus Myth

From the expulsion of the Hyksos to Armageddon, the epic Passover saga does not reflect a specific event, but seems to contain distant memories that may give us clues to the real history of the ancient Israelites

The Passover narrative is one of the greatest stories ever told. More than any other biblical account, the escape of the enslaved Hebrews from Egypt is the foundational story of the Jewish faith and identity, one that all Jews are commanded to pass on from generation to generation.

Also, it never happened.

For decades now, most researchers have agreed that there is no evidence to suggest that the Exodus narrative reflects a specific historical event. Rather, it is an origin myth for the Jewish people that has been constructed, redacted, written and rewritten over centuries to include multiple layers of traditions, experiences and memories from a host of different sources and periods.

Peeling back those layers and attempting to interpret them with the help of archaeology and biblical scholarship can reveal a lot about the actual history of the early Israelites, probably more than a literal reading of the Passover story.

“It’s not a historical event, but it’s also not totally invented by someone sitting behind a desk,” explains Thomas Romer, a renowned expert in the Hebrew Bible and professor at the College de France and the University of Lausanne. “These are different traditions that are brought together to construct a foundation myth, which can be, in a way, related to some historical events,” he says.

Before digging for these kernels of historical truth, you might be wondering whence the assertion that the story of a large group of Hebrew slaves fleeing Egypt for the Promised Land is a myth.

There are multiple points where the Passover story doesn’t square with archaeological findings, but the broader issue is that the Bible simply gets the chronology and the geopolitics of the Levant wrong.

Egypt was here

Scholars have long been arguing about the date of the Exodus, but for the biblical chronology to hold any water, Moses must have led the Israelites out of Egypt sometime in the Late Bronze Age, between the 15th and 13th century B.C.E. – depending on whom you ask.

The problem is that this was the golden age of Egypt’s New Kingdom, when the power of the pharaohs extended over vast territories, including the Promised Land. During this period, Egypt’s control over Canaan was total, as evidenced for example by the Amarna letters, an archive that includes correspondence between the pharaoh and his colonial empire during the 14th century B.C.E. Also, Israel is littered with remains from the Egyptian occupation, from a mighty fortress in Jaffa to a bit of sphinx discovered at Hazor in 2013.

So, even if a large group of people had managed to flee the Nile Delta and reach Sinai, they would still have had to face the full might of Egypt on the rest of their journey and upon reaching the Promised Land.

“The Exodus story in the Bible doesn’t reflect the basic fact that Canaan was dominated by Egypt, it was a province with Egyptian administrators,” says Tel Aviv University professor Israel Finkelstein, one of the top biblical archaeologists in Israel.

This is probably because the Exodus story was written centuries after its purported events and reflects the realities of the Iron Age, when Egypt’s empire in Canaan had long collapsed and had been forgotten.

The fact that the biblical account is anachronistic, not historical, is also suggested by archaeological exploration of identifiable sites mentioned in the Bible. No trace of the passage of a large group of people – 600,000 families according to Exodus 12:37 – has been found by archaeologists. Places like Kadesh Barnea, ostensibly the main campsite of the Hebrews during their 40 years wandering the desert, or another supposed Hebrew campsite of Ezion-Geber at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba were in fact uninhabited during the Late Bronze Age (15th-13th centuries B.C.E.), which was when the Exodus would have happened, Finkelstein says. These locations only begin to be populated between the 9th and 7th centuries B.C.E., the heyday of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

Most scholars believe the earliest versions of the Exodus myth may have been written during this later time: the biblical authors were evidently unaware that the places they were describing did not exist in the period they were setting the story in.

But even Finkelstein cautions that this does not mean we should callously dismiss the Passover narrative as mere fiction. “Exodus is a beautiful tradition that shows the stratified nature of the biblical text,” he says. “It is like an archaeological site. You can dig it layer after layer.”

The Hyksos expulsion

Most scholars agree that, at its deepest level, the Exodus story reflects the long-term relationship between Egypt and the Levant. For millennia, people from Canaan periodically found refuge in Egypt especially in times of strife, drought or famine – just like Jacob and his family do in the Book of Genesis.

Some of these immigrants were indeed conscripted as laborers, but others were soldiers, shepherds, farmers or traders. Especially during the Late Bronze Age, a few of these people with Levantine roots even achieved high office, serving as chancellors or viziers to the pharaohs and appearing prominently in Egyptian texts.

These immigrant success stories have often been seized upon by defenders of the Bible’s historicity for their parallels with the tale of Joseph’s rise to prominence at pharaoh’s court or Moses’ upbringing as an Egyptian prince.

“They do look a bit like Moses or Joseph but none of them would be really fitting as the historical Moses or Joseph,” cautions Romer.

One group of particularly successful immigrants that has often been linked to the Exodus story were the Hyksos, a Semitic people that gradually moved to the Nile Delta region and grew so numerous and powerful that they ruled over northern Egypt from the 17th to the 16th century B.C.E. Eventually, the indigenous Egyptians, led by Pharaoh Ahmose I, expelled the Hyksos in a violent conflict. Already in the 1980s, Egyptologist Donald Redford suggested that the memory of this traumatic expulsion may have formed the basis for a Canaanite origin myth that later evolved into the Exodus story.

While this is possible, it is not clear what the connection was between the Hyksos, who disappeared from history in the 16th century B.C.E. and the Israelites, who emerged in Canaan only at the end of the 13th century B.C.E. It is then, around 1209 B.C.E., that a people named “Israel” are first mentioned in a victory stele of the pharaoh Merneptah.

And in this text, “there is no allusion to any Exodus or that this group may have come from elsewhere,” notes Romer. “It’s just an autochthonous group at the end of the 13th century sitting there somewhere in the highlands [of Canaan].”

Yahweh and the Exodus

So if the Israelites were just a native offshoot of the local Canaanite population, how did they come up with the idea of being slaves in Egypt? One theory, proposed by Tel Aviv University historian Nadav Na’aman, posits that the original Exodus tradition was set in Canaan, inspired by the hardships of Egypt’s occupation of the region and its subsequent liberation from the pharaoh’s yoke at the end of the Bronze Age.

A similar theory, supported by Romer, is that the early Israelites came in contact with a group that had been directly subjected to Egyptian domination and absorbed from them the early tale of their enslavement and liberation. The best candidate for this role would be the nomadic tribes that inhabited the deserts of the southern Levant and were collectively known to the Egyptians as the Shasu.

One of these tribes is listed in Egyptian documents from the Late Bronze Age as the “Shasu of YHWH” – possibly the first reference to the deity who that would later become the God of the Jews.

These Shasu nomads were often in conflict with the Egyptians and if captured, were pressed into service at locations like the copper mines in Timna – near today’s port town of Eilat, Romer says. The idea that a group of Shasu may have merged with the early Israelites is also considered one of the more plausible explanations for how the Hebrews adopted YHWH as their tutelary deity.

As its very name suggests, Israel initially worshipped El, the chief god of the Canaanite pantheon, and only later switched allegiance to the deity known only by the four letters YHWH.

“There may have been groups of Shasu who escaped somehow from Egyptian control and went north into the highlands to this group called Israel, bringing with them this god whom they considered had delivered them from the Egyptians,” Romer says.

This may be why, in the Bible, YHWH is constantly described as the god who brought his people out of Egypt – because the worship of this deity and the story of liberation from slavery came to the Israelites already fused into a theological package deal.

The north remembers

It does seem, however, that as the Israelites went from being a collection of nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes to forming their own cities and states, they did not all adopt the Exodus story at the same time.

The tradition of an Exodus seems to have first taken hold in the northern Kingdom of Israel – as opposed to the southern Kingdom of Judah, which was centered on Jerusalem. Scholars suspect this because the oldest biblical texts that mention the Exodus are the books of Hosea and Amos, two prophets who operated in the northern kingdom, Finkelstein explains.

Conversely, the Exodus begins to be referenced in Judahite texts that can be dated only to after the end of the 8th century B.C.E, when the Assyrian empire conquered the Kingdom of Israel and many refugees from the north flooded into Jerusalem, possibly bringing with them the ancient tradition of a flight from Egypt.

Although geographically Israel was farther from Egypt than Judah, there are a few reasons why this northern polity would have been the first to import a story about salvation from pharaoh as a foundation myth, Finkelstein says.

Firstly, the Tel Aviv archaeologist has recently theorized that there is some evidence suggesting that the Kingdom of Israel formed as a result of the military campaign in Canaan of Pharaoh Sheshonq I in the mid 10th century B.C.E. This campaign was meant to restore the empire Egypt had lost at the end of the Bronze Age, in the 12th century B.C.E., and Sheshonq (aka Shishak) may have installed the first rulers of Israel as petty kings of what was meant to be a vassal state, Finkelstein says.

When Egypt’s imperial ambitions floundered, the northern Israelite polity emerged as a strong regional power, and may have adopted the Exodus story as a charter myth for its own foundation, as a nation once beholden to Egypt but then freed from the pharaoh’s grip, Finkelstein says.

Secondly, as the Kingdom of Israel grew in power, it expanded southward into the Sinai and Negev deserts in the early 8th century B.C.E. The northern Israelites became involved in trade with nearby Egypt, and came into contact with the places and sceneries described in the biblical wandering of the wilderness, Finkelstein says.

At Kuntillet Ajrud, an Israelite site in Sinai, archaeologists have found a treasure trove of texts and inscriptions from this period that give us some clues about the belief system of the northern kingdom.

One of these inscriptions has been tentatively identified by Na’aman as an early version of the Exodus myth.

While the text is fragmentary, it is possible to discern some of the familiar elements of the story, such as the crossing of the Red Sea, but also snippets that contradict the narrative as we know it. For example, the story’s hero, whose name has not survived, is described as a “poor and oppressed son,” which doesn’t jive with the biblical description of Moses’ gilded upbringing as a prince of Egypt.

Exodus sans Moses?

This brings us to the protagonist of the Passover story and the question of his historicity. Scholars have long pointed out that Moses’ origin story is a suspiciously common trope.

From the Mesopotamian ruler Sargon of Akkad to the founders of Rome – Romulus and Remus – the ancient world seems to have been awash in boys who were birthed in secret, saved from mortal danger by a river and adopted, only to grow up to discover their true identity and triumphantly return to lead their people.

It is in fact possible that Moses, at least as we know him, was a fairly late addition to the Exodus story, because he does not appear in northern biblical texts such as Hosea and Amos, says Romer.

The oldest text that mentions him is the story of the late 8th century B.C.E. Judahite King Hezekiah, who, as part of a religious reform, destroyed a bronze serpent purportedly made by Moses that was being worshipped by the Israelites (2 Kings 18:4).

This leads Romer to posit that the Moses tradition originated in Jerusalem and that there may have been an older Exodus story that didn’t include him as a hero.

Some traces of this tale may have survived in the Bible, Romer says. For example, in the fifth chapter of Exodus, there is an entire chunk of text in which Moses and his brother Aaron disappear from the plot, and unnamed “Israelite overseers” appear in charge of the negotiations with the pharaoh and the protestations over the conditions of the Hebrew slaves (Ex. 5:6-18).

“Some think that here we have traces of a divergent tradition in which it was God directly who brought the people out of Egypt, that it was just the people who cried out and Yahweh delivered them,” Romer says.

Josiah heads for Armageddon

Whether or not Moses was in it from the start, the Exodus tradition must have undergone some serious redactions after it was absorbed by Judah in the late 8th and 7th century B.C.E. As mentioned earlier, many of the locations mentioned in the desert wandering narrative were only inhabited during this later period, which in and of itself indicates that much of the text as we know it was written down during this period.

This time, around 2,700 years ago, was a key moment in the history of the ancient Hebrews. By the late 7th century B.C.E., the Assyrian empire, which had conquered the Kingdom of Israel, was itself on the wane. In Jerusalem, King Josiah led a reform to centralize the cult around the Temple, while his scribes compiled early biblical texts using a combination of sources from the northern kingdom and Judah.

The ambitious Judahite ruler was hoping to unite all the Israelites under a single cult and a shared history. He also coveted the former territories of Israel, which were now being vacated by the Assyrians. But this expansionism put him in conflict with none other than Egypt, which was again eyeing a restoration of its empire in Canaan, Finkelstein explains.

So, once again, the saga of the Exodus was put to political use, providing Josiah with a story that would unite his people against an old adversary, an epic tale that promised deliverance from the oppressor and the conquest of a Promised Land.

Things didn’t go exactly as planned for Josiah. The competing policies of expansionism led to a clash with Pharaoh Necho II, who faced Josiah at Megiddo around 609 B.C.E. and killed the Judahite king (2 Kings 23:29).

Ever since, Megiddo – also known as Armageddon – has become the symbol of an apocalyptic end to a messianic dream, ultimately translating into the Christian tradition that locates there the final battle between good and evil at the end of times, Finkelstein says.

But while Megiddo marked the end of Judah’s political ambitions, it was not the end of the line for the Exodus tradition. This beautifully complex story, which is not the record of a single event in time but an echo of a centuries-long confrontation between two ancient civilizations, has continued to evolve and take on different meanings.

Generation after generation, it has inspired Jews – and non-Jews – to resist in the face of overwhelming odds, to value freedom above all and to hope against all hope that the Promised Land is always just around the corner.

Why is this Seder different from all other Seders?

Ira Glunts, Mondoweiss

18 April 2019

The idea of making a different type of Seder came about because of my discomfort with a ceremony that in many ways glorifies Jewish exceptionalism and also serves as a justification for the Israeli dispossession and suppression of the Palestinian people and their culture. Passover now appears to me to be the most Zionist of all Jewish holidays, and its celebration, the reading of the Haggadah, the Hebrew text which defines the Seder, clearly reflects this fact.

The first problem comes at very beginning of the ceremony when the host recites the Kiddush declaring that God chose the Jewish people above all other peoples. This type of exceptionalism is very much out of favor with many these days, as it should be, whether it is applied to Jews, Israel or to American foreign policy.

Secondly, there is the glorification of God’s horrible vengeance upon those who have wronged the Jews or those who do not believe in their God. God’s killing of Egyptian innocent children is awful even as a symbolic tale.

After drinking the third of the four cups of wine, the host instructs the presumably tipsy guests to rise and pour a fourth cup. Referring to God, he then recites from the Psalms:

Pour out Thy wrath upon the nations that know Thee not, and upon the kingdoms that call not upon Thy name; for they have consumed Jacob and laid waste his habitation. Pour out Thy rage upon them and let Thy fury overtake them. Pursue them in anger and destroy them from under the heavens of the Eternal.

A bit over the top, no? Especially, when the present-day real God of many American Jews, Israel and its mighty army, has laid waste to Gaza in a succession of criminal assaults which continue today as a brutal siege and a weekly massacre at the eastern Gaza border. The first Seder this year takes place on a Friday, which is the day of the week most of the border killings occur.

Oh, and one more thing, the Hebrew word for “nations that know Thee not” is “goyim,” which is also the derisive name Jews call non-Jews in their common vernacular. Who wants to say that, even if all your guests speak no Hebrew and may not hear the “g” word?

Thirdly, I recoil at the allusion to the perpetual victimization of the Jewish people which is uttered with only the fortification of one cup of wine.

For more than once have they risen against us to destroy us; in every generation they rise against us and seek our destruction. But the Holy One, blessed be He, saves us from their hands.

This, for me echoes the recent false claims of anti-Semitism from which we are protected, not so miraculously, by the smears of pro-Israel lobby operatives directed at people such as Rep. Ilhan Omar, Jeremy Corbyn or anyone else who criticizes Israel and its apartheid government.

And lastly but very importantly, is the oft-quoted declaration toward the conclusion of the reading of the Haggadah of “next year in Jerusalem.” This phrase is frequently and ludicrously cited as proof of the long-time (2000 year) Jewish longing for return to their homeland, and it is employed as a justification for the entire Zionist enterprise.

This is ironic because the “telling” (haggadah) of the exodus story is especially irksome since most people actually believe in its veracity as recorded history even though this story has absolutely no basis in fact. There is actually zero historical evidence that the Jews were ever slaves in Egypt.

Passover, as with all Jewish celebrations in Israel, means “closure” for the Palestinians under occupation. That entails restricted travel and other prohibitions which make the lives of the Palestinians even more difficult than normal.

As they say in another context in the Haggadah, “dayenu?” or “is that not enough?” to explain why an alternative Seder may be in order. For me it is more than enough.

So here is what I have come up with as a replacement.

My Seder is called a seder lo b’seder, or loosely translated, a Seder that is not right or not OK. It sounds better in Hebrew. It is held on the second day of Passover and may serve as an antidote for guests who have participated in a traditional Seder the previous evening. Seder means arrangement or order and lo means not. So this is a Seder with no order, the opposite of the meaning of Seder and the tradition of doing the ceremony in a proscribed manner.

My motto is “skip the (traditional) Seder, do a Seder lo b’Seder.” The Hebrew verb for skip is the same as the name of the holiday. Just as Passover, i.e., pass over, in English, is synonymous with skip.

Thus there is no order in which the meal is to be eaten. All foods from soup to dessert will be available to the guests throughout dinner. All can eat what they want when they want and just as importantly not eat what they do not desire.

Some usual Passover foods will be available. They include gefilte fish, matzoh (the cracker that is central to the symbolism of Passover), red wine and grape juice. Also, charoset which is a mixture of nuts, dried and fresh fruits, nuts and honey because it tastes really good. Bread and shrimp (prohibited by Jewish law during Passover) will also be available and are placed in close proximity to the matzoh and gefilte fish, respectively.

Italian food which is a popular cuisine in my upstate New York community, since there is a large Italian-American presence here, will be featured. The main courses will be a vegetarian lasagna and Utica greens which is a popular indigenous local dish invented by my sister-in-law’s cousin.

Instead of the traditional not consumed glass of red wine for the prophet Elijah, a glass of wine will be placed on the table in memory of my dear departed friend and neighbor, Bruce, who would have been a willing enthusiastic participant in this Seder.

The only restriction placed on the food that is acceptable at this Seder is that it is not wholly or partly produced at Israeli companies. This Seder is officially and proudly designated as a pro BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) event. Luckily, neither this Seder nor anything I or my wife do is funded by the State of New York because the New York State governor, Andrew Cuomo, has bowed to the pro-Israel lobby, or as it is known in Israel, the Jewish lobby, and cut state funding to all supporters of BDS.

Chad Gadya at Seder lo b’seder

The only part of the typical Seder that is included in the seder lo b’seder is the performance of the song Chad Gadya which ends the festive meal. In my Seder the song is performed both before and after dinner. Prior to eating, the guests are invited to listen and view a video (with English subtitles) of the Chava Alberstein (Hebrew Wikipedia entry) version of this iconic Passover song which she recorded at the height of the First Intifada in 1989. In this rendition, which is sung mostly in Hebrew instead of the more traditional Aramaic, Alberstein added protest lyrics in response to the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestinian land. Echoing the words of the Haggadah she sings,

And what has changed for you?

What has changed?

I myself have changed this year

And on all nights, on all nights

I have asked only four questions

Tonight I have another question:

How long will the cycle of horror last?

… Hunter and hunted, beater and beaten

When will this madness end?

Alberstein’s protest song roiled much of the Jewish Israeli population and it was banned from the radio despite or maybe because of the enormous popularity and artistic reputation of the singer. Younger readers will take note that the suppression of speech critical of government policy, especially in relation to what goes on in the territories, did not start with Netanyahu.

Chava Alberstein song

A couple of weeks ago I came across a video of the Rana Choir performing an Arabic/Hebrew version of the Alberstein Chad Gadya at a 2016 Arab-Israeli Remembrance Day Ceremony. The choir is a group based in Jaffa, composed of Palestinians and Jews, which is unusual in Israel. I am usually rather skeptical about joint ventures in the apartheid reality of Israel which are derisively and understandably termed “normalization” by many Palestinians. Most end up with members of the stronger group, the Jews, setting the agenda, and ironically reproducing the unequal power relationship of the occupation. I have been told that the Arabic is almost unintelligible. However, despite all this I will present this version to my guests as a possible source of hope. This beautiful and haunting once censored protest song is, at least, still being performed.

Menu at Ira Glunts’s Seder

As in the “normal” Seder, the meal and ceremony concludes with the host, me, singing Chad Gadya with the guests invited to join in. They are especially encouraged to, at the very least, sing the chorus. The song in our Seder is sung in Aramaic as is usual.

I like this song because it arguably is understood as having no significant meaning and as being pure melody and wordplay. In other words free of the cant, rant or any political significance of which I may find objectionable but ever present in the normal Seder.

So that is the outline of my planned Passover meal. It is an attempt to quietly declare that Zionism is not tenable or moral and rites of Judaism that support Israel are also not tenable. I do not mean my Seder to be offensive to any of my fellow co-religionists, but if it is so be it.

In our American culture those who renounce Catholicism are not generally censured by the general population, but those that criticize practices of Judaism that serve Zionism are. Why is that?

Unfortunately, my Seder will not happen this year due to family commitments having nothing to do with Passover. However, I plan to do it next year. The guests will include my 94-year-old mother-in-law and her daughter, my wife’s sister, both of whom attended my initial alternative Seder two years ago. My wife and her family are not Jewish; however all told me they had a wonderful time. I already have three dear friends who are pro-Palestinian activists committed to the event. Two of them will be recovering from the previous night’s first Seder. All three have been falsely accused of anti-Semitism by the local Jewish Federation in response to their political activity.

Zionism means dispossession of 700,000 indigenous Palestinian people and their future descendants. Today it means the ever-expanding Judaization of Jerusalem, the oppression of the Palestinian people including the brutal siege of Gaza and the continual killing of Gazans at the border protests.

That is why I say, “Next year in upstate New York, I will have a seder that will be lo b’seder.”