Josiah Wedgwood MP and his support for Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany

JVL Introduction

Josiah Wedgwood MP became one of the most determined opponents of appeasement after Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933. He campaigned vociferously for those seeking to escape persecution in Nazi-occupied Europe to be given refuge by the British government, a challenge it refused to meet.

In this article Lesley Urbach gives him the recognition he so richly deserves.

First published in the AJR Journal (Association of Jewish Refugees) and reposted here with the author’s permission,

‘For our honour’s sake we dare not keep them out’

Josiah Wedgwood and the Jews in Nazi-controlled Europe, 1933-1939

Lesley Urbach, Association of Jewish Refugees Journal

March 2109, pp.4-5

Reposted with the author’s permission

After representing the Liberal Party and then sitting as an Independent Radical MP, he joined the Labour Party in 1919. He was elevated to the Peerage in 1942, sitting in the House of Lords until he died in July 1943.

During his parliamentary career Wedgwood campaigned on issues such as home rule for India, the creation of a British Commonwealth based on shared principles of democracy and equality, the taxation of land value, the creation of a biographical dictionary of Members of Parliament, and the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine as part of a British Commonwealth. In March 1936 the Jewish Chronicle called Wedgwood ‘one of the earliest and most zealous friends of the Zionist cause’ and thanked him ‘from our hearts’.

Wedgwood became one of the most determined opponents of appeasement after Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933. He vociferously campaigned for those seeking to escape persecution in Nazi-occupied Europe to be given refuge in the Colonies and Palestine and Britain. This article focuses on his calls that the Jews be allowed into Britain between 1933 and the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939.

At the end of March 1933 Wedgwood, addressing a meeting of the Anglo- Palestinian Club, urged Britain to welcome and absorb the persecuted Jews of Europe and to make ‘Palestine a haven of peace for them’. Britain, he declared, needed to ‘show the world what was decent behaviour and their reprobation of what was not decent behaviour.’

On 13 April 1933, speaking in the House of Commons, he suggested that it was Britain’s duty to grant hospitality to the oppressed whatever ’the Prussian Aryan may feel about the Jews, or the peace-mongers or even the Socialists.’ Just over a month later the Home Secretary did not respond when Wedgwood asked whether the British government was going to do anything to help the people who were being persecuted in Germany to escape even though their situation worsened each day. He continued to make such statements and ask parliamentary questions up to and beyond the start of the Second World War. He asked for visas on behalf of individuals as the war drew nearer. His last appeal, before the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939, for a permit for a Frau Lasmann, destitute in Poland after being expelled from Germany, was turned down.

However, Wedgwood was always going to have little success in his efforts to secure refuge for the Jews as Britain’s immigration policy, established by the 1905 Aliens Act and the 1919 Aliens Restrictions Amendment Act, ruled out the entry of aliens for permanent settlement. There was no legal obligation on the government to admit refugees. The only people allowed permanent entry were those whose presence offered some benefit to the country, or people with strong personal or compassionate reasons. Entry did not become easier as the persecution grew in Germany and spread to Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939 respectively, although certain additional categories of people were allowed temporary asylum such as those ready to be domestic servants, unaccompanied children and in the case of Czechoslovakia, political refugees. Britain’s national interests were put ahead of humanitarianism before and during WW2. Wedgwood did not, he declared in July 1936, ‘like the part which England had played in the refugee question.’ Despite his ceaseless efforts on behalf of the persecuted Jews and socialists, his opinion was not to change over the remaining seven years of his life.

Wedgwood disliked injustice and cruelty and in November 1933 he told a meeting that he saw all that was going on in Germany as ‘a vast moral evil violating justice.’ And 30 months later he described Germany as a country without justice where people seemed to have been transported back to the fifteenth century. While the government’s position was that asylum could only be given if it was in the country’s interests, Wedgwood believed that one should ‘do justice though the Heavens fall… it ought not to be a question of expediency but of justice.’ One could, he continued, justify any actions in the interests of the state, ‘people had been burned at the stake in the interests of the state.’ In May 1934, he told the House of Commons ‘I am not pro- Jew, but pro-English, I set a higher value on the reputation of England all over the world for justice than for anything else.’

Wedgwood regularly argued that Britain had to help the Jews for the sake of its reputation for hospitality, generosity and liberty, telling MPs in April 1933 ‘Get these people in, and get them here to strengthen our home and our love of liberty.’ After Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938, Wedgwood proposed that Austrian Jews be allowed into Britain and be naturalised. He reminded his fellow MPs that while they were sitting there in peace, all Jews, rich as well as poor, were suffering terribly and gave an example of a Jewish woman being made to scrub the streets with her tongue while crowds of Austrians looked on and jeered. ‘We cannot conceive of these things…for our honour’s sake we dare not keep them out.’ His proposal was rejected by the House.

A year later, in a speech described by the Sheffield Telegraph as ‘notable for its undercurrent of emotion’, Wedgwood read out a letter from a young Jewish Viennese woman pleading for a telegraphed visa for herself and her four-year-old child. Her husband was in a concentration camp and they were without money or food. ‘People like these,’ Wedgwood exclaimed, needed to be given refuge and ‘not allowed to die of starvation … Surely, we in this country might do something to help these people here,’ he begged. ‘To do nothing and leave these people to die or languish in concentration camps because no country would take them in time should fill the average Englishman with a feeling of pity and shame.’ In another speech, he said that if people actually saw the Jews begging in Regent Street he was sure ‘the heart and conscience of England would be moved to do better than we are doing.’

Wedgwood believed that refugees and immigrants benefited the country and he described the view that refugees would take jobs and food from British people as ridiculous, uncharitable and ignorant. He pointed out on several occasions that refugees created as many jobs as they took. ‘It is not by national selfishness that the problem of unemployment will be solved,’ he wrote in March 1939.

Wedgwood condemned Britain’s restrictive immigration policy and the blockages in the system which slowed down or prevented the entry of the desperate refugees. In April 1939, referring to one of the many people he could not help, Wedgwood told the House that there were thousands of people who were huddling in doorways, hoping to come to England; yet the restrictions made it impossible for anyone without money or contacts to get out. Given that the Nazis had taken away the Jews’ money, he asked ‘What can we expect these millions of poor people to do?’

He was infuriated when the government blamed the voluntary groups involved with the refugees for any failures in the immigration system, telling MPs in April 1936 ‘There is too much of this desperate attempt by the Government to put the blame on somebody else. They are responsible for the visas and for the conditions under which these people come to this country.’

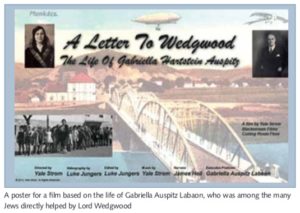

Wedgwood himself paid the guarantees for over 200 individuals of £50 each (approximately £3200 in today’s money) and housed many at his home in Staffordshire. Dr Theresa Steuer, an Austrian refugee who, along with her husband, was guaranteed by Wedgwood, paid tribute to him at public meetings on several occasions. The biography of Gabriella Auspitz Labaon, a Jewish woman from the Carpathian Mountains whom he saved together with her brother, is entitled, My Righteous Gentile: Lord Wedgwood and other Memories. In it she writes extremely warmly about Wedgwood’s hospitality and support for her.

In May 1934 Wedgwood was founding chairman of the German Refugee Hospitality Committee. From December 1938 he sat on the newly established Parliamentary Committee on Refugees. Wedgwood continued to campaign for the Jews after the outbreak of the war, particularly arguing that they should be allowed into Palestine. Together with Eleanor Rathbone he led the calls for the end of internment of the refugees detained in Britain, Austria and Canada.

While a Foreign Office official wrote that Wedgwood was hopelessly unbalanced on the subject of supporting the Jews, the United Jewry Fellowship called him ‘one of their greatest non-Jewish friends in the British Parliament’. And Dr Joshua Stein writes that ‘it is certainly likely that Wedgwood’s constant harping helped to establish a climate whereby it became more acceptable to help the Jews.’

Like Eleanor Rathbone, Wedgwood’s name and efforts on behalf of European Jews deserves to be remembered and honoured by the Jewish community. Unfortunately it is not, while the image of the generosity of the British government continues to be upheld.

Lesley Urbach

While Wedgwood is to be commended for his humanitarian motives in wanting to relieve the pain and suffering of Jews in mainland Europe, he never once mentions the people already living in Palestine.

This kind of colour-blindness was not unique to him.

The Palestinians living in British Mandate Palestine were almost universally ignored.

They were un-persons.

So, while I can understand the debt of gratitude towards him from many Jews – especially ones he helped to save – I cannot understand why his attitude towards the indigenous Palestinians is not subject to greater scrutiny.