Is censoring only one side of the Israel-Palestine debate justified?

JVL Introduction

The motivation of supporters of Palestinian rights is routinely questioned by pro-Israeli advocates because some of them may also harbour negative attitudes toward Jews.

Why are such standards not applied to supporters of Israel, among some of whom there is evidence of anti-Muslim sentiment?

In fact is there any real justification for increasing attempts at censorship from Israel and its supporters, or should free speech be respected by both sides?

Dr Alan Maddison looks at the evidence and teases out the double standards involved.

Dr Alan Maddison writes

Israel advocacy groups have sought to stigmatise and censor support for Palestinian rights arguing that some of Israel’s critics also harbour negative attitudes toward Jews.

At the same time, even the possibility of the presence of anti-Muslim attitudes in some supporters of Israel has been largely ignored.

It seems wrong that such censorship should only apply to one side of such an important debate, involving Israel’s human-rights violations.

Whilst there are clearly many opinions on the Israel-Palestine conflict that will not be built on prejudice, we must consider the thesis that some views will be affected by negative sentiments towards either Jews or Muslims.

How widespread is it? Let’s look at the available evidence.

Prejudice and opinions on the Israel Palestinian ‘conflict’

A survey of the opinions of Britons (1) on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict showed that 18% of respondents were more sympathetic towards Palestinians and 6% towards Israelis. The distribution of all views is shown below.

Whilst there are no doubt legitimate reasons for most of these above views, we want to know what proportion may be associated with animosity towards either Muslims or Jews.

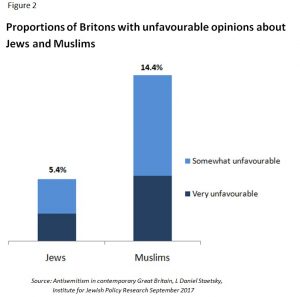

As the respondents in Figure 1 are representative of the whole British population then we would expect overall prejudices to be similar to those illustrated in Figure 2 below.

In the above survey we see that there are almost three times more people with anti-Muslim than anti-Jewish animosity in Britain, and a similar ratio is found in similar surveys (1-3).

It has to be said that such associated prejudices may not all influence views on Israel-Palestine, nor would they necessarily be expressed as abuse during debates/comments. However, it is reasonable to consider the risk for both is clearly around three times higher for associations with anti-Muslim than with anti-Jewish sentiment.

From this there appears no justification for the overwhelming focus on censorship relating to associated antisemitism, while that associated with Islamophobia is totally ignored.

However, this 3:1 ratio may not hold for more partisan sub-groups in Figure 1, those with distinct sympathies for one side, and who may be more likely to participate in debates or exchanges on Israel-Palestine. What can we say about them?

Prejudices in those more sympathetic to Israelis or to Palestinians

One might expect that anyone with a particular dislike for Jews would tend to have more sympathy for Palestinians and vice versa, resulting in higher shares of prejudices in such partisan groups than for the whole population.

There is indeed evidence that the prevalence of antisemitism can increase to a level of up to 17% in those endorsing certain statements critical of Israel (4,5).

The reasons for such an increased association with antisemitism are not clear. For some a ‘pre-existing animosity towards Jews’ may have led to their subsequent strong criticism of Israel. For others an ‘initial hostility towards Israel’s treatment of Palestinians’ may have generated their antisemitism, through conflation. For some there may be no motivational link at all, just a chance association relating to a prejudice towards British Jews.

We may then ask if a similar amplification of associated anti-Muslim sentiments would be found in strong supporters of Israel.

This seems likely.

For instance, Israel positions itself as a rampart and indispensable ally against Islamist terrorism.One of the reasons given for disliking Muslims in Britain is the false belief that the majority of them support Islamist terrorist violence. It appears thatin reality only 2% of British Muslims do, fewer than the 4% found in the general population (6), yet the false negative stereotype remains widespread.

So, a greater tendency for those people with Islamophobic prejudices to support Israel would be expected, even if related to a false premise.

This is especially true for the far right, traditionally with very high levels of prejudice towards both Jews and Muslims. Many, such as the former leader of the EDL (Tommy Robinson), openly support Zionism and Israel, seemingly as they perceive the greatest threat for the moment to their view of the world is from Muslims.

I could find no publications quantifying the probable link between preferential support for Israel, or Israelis, and anti-Muslim sentiment. However, in an article in the Washington Post (7) the journalist Michael Tesler did write about incidents of Islamophobic abuse from supporters of Israel, and remarked that it was a curiously neglected issue.

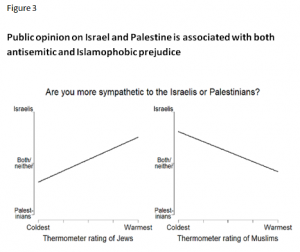

He illustrated an American survey (Figure 3) which showed increasing support for Israelis as opinions about Muslims ‘cooled’, and increasing support for Palestinians as opinions about Jews ‘cooled’.

The similar gradients of the two lines, albeit inverted, suggest that the relationships between opinions on Israel-Palestine and anti-Jewish or anti-Muslim attitudes follow the same dynamics of amplification with increasing sympathies for each side.

Such American ‘thermometer surveys’ (8,9) have shown the ratios of anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish attitudes in the United States are similar to the 3:1 reported in Britain.

It is reasonable to expect a similar pattern of dynamics in Britain, even if there is less support for Israel here, so we would find the same degree of amplification of prejudice, above the population baseline illustrated in Figure 2, for both anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish sentiments in those with strong sympathies for each group.

The significant finding is that the anti-Muslim attitudes will probably continue to be three times more prevalent than anti-Jewish attitudes across the Palestinian-Israeli preference spectrum, including those people with the most partisan views.

If the antisemitism prejudice can rise from 5.4% (Figure 2) up to 17% as mentioned earlier, then Islamophobia should rise in proportion from 14.4% up to 45% as illustrated below.

This means that, depending upon the mix of participants for any exchange or debate on Israel- Palestine, we could expect to find a range of antisemitism between 5% and 17% in supporters of Palestine and of Islamophobia between 14% and 45% in Israel supporters.

The scale of abuse during debates on Israel-Palestine

From the figures in Table 1, it would follow that supporters of Palestinian rights are likely to face the greatest risk for abuse.

Of those responding to a survey saying they may have a ‘somewhat negative’ or a ‘very negative’ opinion’ about Jews or Muslims,only a small minority will manifest such prejudice in terms of abuse.

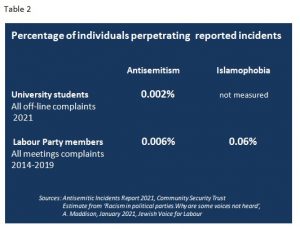

We don’t have precise information on such manifestations during meetings or exchanges on Israel- Palestine, but we do have some broader data to guide us, involving university students and Labour Party members, as shown in Table 2 below.

In Table 2 we see the results from a recent survey (10,11) of universities in which antisemitic incidents were reported over a 12-month period in 2021. There had been 128 allegations of antisemitism reported, covering 164 university institutions with a total of 2.8 million students. Of these allegations, 53 were offline and these would have represented reported manifestations from just 0.002% of students as shown above.

No similar survey data were found for Islamophobic abuse on campuses.

In addition, we previously estimated, from publications concerning the Labour Party (12), that between 2014 and 2019 there were about 30 reported complaints of antisemitism, and 320 of Islamophobia originating from all Labour Party meetings of which there were about 20,000 each year.

This would reflect manifestations of alleged antisemitism involving 0.006% of 500,000 Labour members, and for Islamophobia ten times more at 0.06%, as illustrated in Table 2.

We do not know how many of these allegations, involving both university students and Labour Party members, concerned debate or exchanges on Israel-Palestine. But even allowing for under-reporting, very few people holding related prejudices seem to manifest them.

Conclusion

We have shown that animosity towards Muslims is estimated to be about three times more prevalent in groups supporting Israelis than anti-Jewish attitudes in groups supporting Palestinians.

The data we have presented suggests that, despite amplified levels of prejudice, manifestations of abuse during debates or exchanges on Israel-Palestine thankfully are infrequent.

There is no convincing evidence that Israel advocates are at greater risk from offensive comments, in fact the risk seems highest for supporters of Palestinian rights.

Therefore, there appears to be no justification for the current disproportionate censorship or stigmatisation of supporters of Palestinian rights.

As in all debates, any abusive comments that occur, whichever side they are from, should be condemned – and sanctioned if necessary.

But it would be wrong, in our democracy, to suppress the expression of most opinions, which are free from any prejudice, and may contribute to finding necessary changes that satisfy both sides.

- Antisemitism in contemporary Great Britain: A study of attitudes towards Jews and Israel, L. Daniel Staetsky, JPR Report, 2017

- Europeans Fear Wave of Refugees Will Mean More Terrorism, Fewer Jobs, Richard Wike et al, Pew Research Center, 11 July 2016,

- Minority groups, Richard Wike et al, Pew Research Center, 14 October 2019

- The apartheid contention and calls for a boycott, David Graham and Jonathan Boyd, JPR January 2019

- The New-Antisemitism: proof at last?, Jamie Stern-Weiner and Alan Maddison, JVL, 24 February 2019

- A Review of Survey Research on Muslims in Britain, Ispos Mori, Social Research institute, February 2018

- Anti-Semitism is linked to public opinion about Israel. But so is Islamophobia., Michael Tesler, Washington Post, 12 March 2019

- How Americans Feel About Religious Groups, Pew Research Center, 16 July 2014

- Americans Express Increasingly Warm Feelings Toward Religious Groups, Pew Research Center, 15 February 2017

- Antisemitic Incidents, Report 2021

- Antisemitism on campus negligible, Derek Taylor, Jewish News/Times of Israel Blogs, 20 November 2021

- Racism in political parties: Why are some voices not heard?, Alan Maddison, JVL, 26 January 2021

A bit late in commenting Alan, but I am tucking away this valuable analysis for future reference. It is good when the empirical confirms the anecdotal. What I find noteworthy and reflected in your analysis is the extent of the success of political lying in exagerating the amount of anti-Semitism as perceived by the general public , whilst the far greater problem of Islamophobia is barely appreciated at all by Joe Public.

The dreadful role of the MSM in parroting the lies of bodies like the BoD and JC here I see is paralleled in South Africa https://www.jewishvoiceforlabour.org.uk/article/hats-off-to-the-south-african-constitutional-court/