In Memoriam: Altab Ali

The annual Altab Ali commemoration takes place 6pm tonight, Friday 4th May, at Altab Ali Park, Whitechapel Road (corner of White Church Lane), E1 7QR

On the 40th anniversary of the murder of Altab Ali, David Rosenberg looks back at the event, the reactions and what we have learnt from it all.

Every year a memorial event is held at Altab Ali park. Image by Shamsuddin Shams

The racist killing of Altab Ali 40 years ago today

Hammer attacks, punctured lungs, slashed faces… far-right groups inflicted a decade of violence on East London’s Bengali communities. In the deadly year of 1978 Bengali youth began the fightback.

David Rosenberg, Shine a Light/OpenDemocracy

4 May 2018

Just east from Whitechapel High Street in the London borough of Tower Hamlets, there is a garden with an ornate entrance. A tubular-framed arch merges with a Bengali-style, orange-coated metal structure. Altab Ali Park is London’s only park named after a Bengali. Previously called St Mary’s Gardens, it was one of several green spaces in Tower Hamlets named after saints.

Altab Ali was neither saint nor sinner, but an immigrant clothing worker who arrived as a teenager in London with his uncle in 1969. He worked in Hanbury Street, off Brick Lane, where the Bengali community was expanding as the older Jewish immigrant population receded. Members of my own family lived in Hanbury Street before World War Two.

Ali returned to Bangladesh for five months in 1975 and got married. When he came back to England, his bride stayed with his parents. The plan was that she would join him later. She never did.

On 4 May 1978, as Ali, 24, walked home from work along Adler Street, alongside St Mary’s Gardens, he was attacked and stabbed by three teenagers, whose minds had been poisoned by racists. Later at their trial they would say they attacked Ali because he was a “Paki”.

Ali was dead on arrival at London Hospital (since renamed the Royal London hospital).

The day Altab Ali died was local election day. The far-right National Front, formed in 1967, ran in every Tower Hamlets ward that year, and gained nearly 10 per cent of the vote. Some older National Front members had been in Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, which terrorised East End Jews in the 1930s.

At 10pm, as the polling booths closed, Shamsuddin Shams, who worked a few doors down from Ali, heard the shocking news. Hours earlier Ali and Shamsuddin had chatted in the street, as they often did after work. On Saturdays, clothing workers usually skipped their lunchbreak so they could finish work at 4pm. Ali and Shams would then meet in Jim’s Café, which was between their workshops, and watch wrestling on Jim’s television.

On 4 May, Shams, then just 18, had gone straight to the polling station on Brick Lane after work. “As I came out I wanted to tell someone. I saw Altab Ali coming out of the Indo-Pak grocery store at No. 45. He had two bags. One had a tiffin box with his evening meal and one had vegetables. He said to me: ‘It must be your first vote. How was it?’ I said ‘It was fine’. I asked him if he had voted yet, and he said he would do it later.”

Shams was devastated by Ali’s death. And initially puzzled. He hadn’t known that Ali had recently moved to Wapping and had taken a different route home that evening.

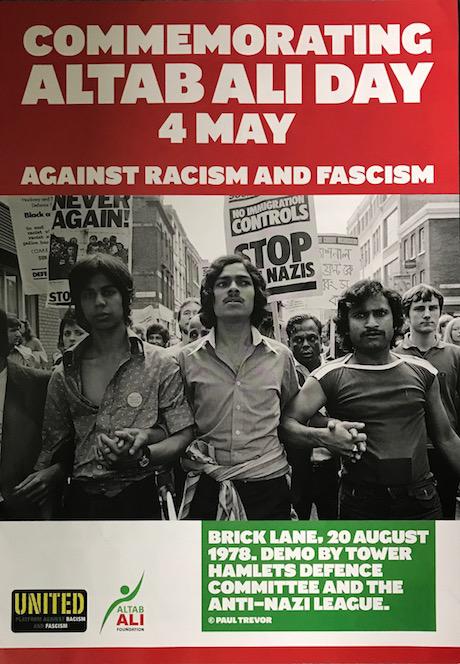

Anti-National Front Demo, Brick Lane 1978. Image by Alan Denney, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Ten days later, local restaurants and workshops across Tower Hamlets were closed up as 7,000 Bengalis marched to Downing Street and Hyde Park. They marched silently in the rain, behind a vehicle carrying Altab Ali’s coffin.

Their placards read: “Self-defence is no offence” and “Here to stay, here to fight”. The militant response to Altab Ali’s murder, led by Bengali youth movements, was a turning point for local Bengalis. As they rallied in Hyde Park they chanted,

“Who killed Altab Ali?”

“Racism, racism!”

Fascists and skinheads on the rampage

On the 40th anniversary of this tragedy, it is salutary to recall the chain of events that led to Altab Ali’s murder. The 1971 census records 161,000 people living in Tower Hamlets. Ten years later that dipped to 139,000, even though 15,000 Bengalis, working mainly in clothing workshops and catering, settled in the East End in that decade. Old factories had closed. A declining dock industry shrank further. Those exiting the borough were mainly white.

Far-right organisations highlighted the rapid cultural and demographic changes. A section of East End dockers joined with Smithfield Market meat porters in 1968 and marched to parliament to support Enoch Powell’s racist “Rivers of Blood” speech. Danny Harmston, who led the Smithfield porters, had formerly been Oswald Mosley’s bodyguard.

Young skinheads began to intimidate new Asian immigrants. In a study of racial tensions in 1970s East London, Reverend Ken Leech said the term “Paki bashing” was invented on Bethnal Green’s Collingwood Estate.

In April 1970, two Asian hospital workers were attacked near the estate after work. The Observer newspaper wrote: “Any Asian careless enough to be walking the streets alone at night is a fool.”

Days later, Tosir Ali, a Wimpy Bar worker, was attacked by two skinheads on his way home. They slit his throat and left him to die. Later that month 50 skinheads rampaged down Brick Lane causing mayhem.

“Any Asian careless enough to be walking the streets alone at night is a fool.” Observer editorial

Initially, the skinheads were not politically organised, but attacked those they considered vulnerable. This included new immigrants. By the mid-1970s, the National Front were actively recruiting skinheads especially in the East London neighbourhoods of Shoreditch and Bethnal Green, where they recorded relatively high votes in the 1974 general election.

A thuggish local orator, Derrick Day, attracted youth to street meetings. In September 1975, hundreds joined an “anti-mugging” march, blaming Blacks and Asians for street robberies.

A year later National Front locals established a regular Sunday morning sales pitch at the corner of Brick Lane and Bethnal Green Road, which attracted supporters from Essex and Kent.

On its books stall, just outside a Jewish-owned shop, you could purchase “Did 6 Million Really Die?” by National Front activist Richard Verrall.

Vile racist stickers from far-right rivals, the British Movement, appeared on lamp-posts. The Hitler-worshippers of Column 88 sent threatening personal messages to local anti-fascist activists, written in blood.

But it was the blood of minority communities that flowed in East London in 1978. Two weeks before Altab Ali’s murder, 10 year old Kenneth Singh was stabbed to death by racists in Canning Town.

Less than two months later Ishaque Ali died of heart failure after a vicious attack by racists.

In September 1978 the National Front moved its headquarters from the suburbs to Shoreditch in East London.

Threatening messages were sent to local anti-fascist activists, written in blood

Two prominent politicians had further inflamed the atmosphere. Tory opposition leader Margaret Thatcher told a TV interviewer in January 1978, that people were “afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture”.

Fear of being “swamped” would make people “hostile to those coming in.” She explicitly confirmed her desire to bring National Front voters “very much back” to the Tories.

Enoch Powell, by now an ageing Ulster Unionist, was still invited to address Tory branches on immigration. On 10 June 1978 he told supporters in Billericay, Essex: “Violence does not break upon such a scene because it is willed, or contrived… it lies in the inevitable course of events.”

He predicted that within 20 years one third of Britain’s inner cities would be controlled by an alien population, “which by reason of the the strongest impulses and… human nature, neither can, nor will be identified with the rest… those who… feared they would be swamped… will be driven by equally strong impulses and interests to resist and prevent it.”

The very next day 150 National Front-supporting white youths, mainly skinheads, translated these words into action. They rampaged down Brick Lane chanting race hate slogans, throwing bottles, bricks and rubble through shop windows. Bengali youths resisted, kettled 20 of the perpetrators and held them until the police arrived. Only three were arrested.

At the same time two heartening events occurred: young people resisted and Bengali shopkeepers received support from neighbouring Jewish shopkeepers.

“There will be fewer cases of friction if races lived separately”

Julie Begum was born in 1968 to Bengali immigrants on the Chicksand Estate off Brick Lane. She remembers what it was like growing up in Tower Hamlets during this period.

“You went to school, you went home, you didn’t hang around, you did your shopping and you hoped that you were not going to be attacked on your way there or back.”

Families like Julie’s were gradually getting places on local housing estates, but one social worker who worked in the area at the time, says: “Asians form a mere 2% of inhabitants in the more pleasant Spitalfields estates… older more tawdry blocks now have Asian populations of 50% or more.”

Discrimination by landlords and racial harassment on run-down estates prompted the creation of the Bengali Housing Action Group which campaigned for better housing and supported Bengali families who felt they had no option but to squat. Local white left wing squatters supported them.

Margaret Thatcher said people were afraid Britain might be swamped by people with a different culture

Altab Ali’s murder motivated the Conservative-controlled Greater London Council (GLC) to address Bengalis’ safety concerns and housing needs.

Without consulting properly, the GLC prepared a hare-brained scheme to designate some estates Bengali-only. The GLC’s Labour minority was split. They wanted to protect Bengalis from racism but were worried about isolating them further. The media ran sensationalist headlines:

“Labour split over GLC Ghetto plan” Evening Standard

“Time Bomb in Ghetto” Sunday Times

And the Daily Telegraph liked the idea: “…there will be fewer cases of friction if races lived separately”.

Jean Tatham, then GLC Housing Chair, defended the plan at an angry community meeting at the Montefiore Centre in Hanbury Street. She told residents that she would make the same offer to all-white and all-Caribbean groups. Eventually the plan was dropped.

Blood on the streets

Shortly after Tosir Ali’s murder back in 1970, Cllr. Solly Kaye, a Jewish communist who fought fascists in the 1930s East End, told a protest meeting: “The purveyors of racialism can be defeated by united action… it would be the greatest error if the struggle were left to the immigrant organisations to bear the brunt of the fight.”

That unity across ethnic and religious divides showed itself when racial violence peaked in the East End between 1976-78. The mainly white trade unionists of Bethnal Green and Stepney Trades Council began compiling a dossier of racist attacks. They gathered information from Avenues Unlimited, a local youth project, Tower Hamlets Law Centre, the Bangladesh Welfare Association, and Brick Lane Mosque.

The mosque’s secretary, Gulam Mustafa, who was Altab Ali’s employer on Hanbury Street, recorded 33 incidents in the first four months of 1978. The dossier was published as a report in September that year with the title “Blood on the Streets”. It listed hammer attacks, stabbings, punctured lungs, slashed faces, airgun shot wounds, people beaten with bricks and sticks and knocked unconscious in broad daylight.

Trade unions were well represented in the Anti-Nazi League formed in 1977. Just four days before Altab Ali’s murder, the league had marched from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park on the Hackney/Tower Hamlets borders. There the marchers combined with Rock Against Racism, which was formed in 1976. They held an anti-racist carnival that brought black and white youth together in a crowd of 80,000 people.

Bengali victims of racist attacks found themselves charged with carrying offensive weapons, and subjected to immigration checks.

The dossier excoriated police failures to investigate attacks and protect victims. Bengali victims of racist attacks found themselves charged with carrying offensive weapons, and subjected to immigration checks.

On 13 August 1976, when six Bengalis were attacked by 25 youths in Brick Lane, no attackers were charged but one victim was. In response the Anti-Racist Committee of Asians in East London, formed earlier that year, held large meetings at Brick Lane’s Naz Cinema, and organised sit-down protests outside local police stations.

Eventually the local police opened a mini-police station for reporting racist incidents, staffed by a police officer and an interpreter, at one end of Brick Lane. But the police failed to properly consult the community before opening the station.

If they had, people would have told them to locate the reporting station at the other end of Brick Lane where local skinheads regularly gathered before launching attacks. Locals were furious and protested against the police’s misplaced intitiative.

A new generation of young cockney Bengalis

The growing unity against racism across East London communities was expressed after a further tragedy, which took place almost a year after Altab Ali’s death on St Georges’ Day 1979.

The National Front announced it would march through the mainly Sikh area of Southall, west London. East London anti-racists joined a counter-protest. One of their number did not return.

The counter protest was brutally policed. Special Patrol Group units were especially violent. They operated in groups of six and were reputed to use illegal weaponry. Blair Peach, a 30 year old New Zealander who taught in Bow, was struck on the head and suffered a fractured skull. He was rushed to hospital but never regained consciousness.

Trades Council secretary, Dan Jones, recalls the late 1970s in the East End as “full of death, marches, and funeral processions… I remember the massive outburst of grief and the dignified defiance by Bengali workers that followed [Altab Ali’s] murder. I remember my friend Blair Peach… who died at the hands of the police in the Southall disturbances. 10,000 of us, black, white, Sikh, Muslim, Christian and Jew gathered in the bleak East London cemetery for his burial.”

But Jones also saw positive signs: “A new generation of young cockney Bengalis was emerging, no longer prepared to cower in fear or to accept discriminatory treatment.” They had “begun to make a fundamental political and social impact on our area.”

40 years on… gentrification and gangs

Forty years on, xenophobia is again on the rise nationally and in East London Bengalis face new challenges. Shamsuddin Shams, now a Brick Lane restaurateur, maintains contact with Altab Ali’s family when he visits Bangladesh. But here he feels the pressure of competing businesses in East London, an area that is fast gentrifying.

The streets to the west of Brick Lane, which once housed Bengalis in multiple-occupancy flats above workshops, have become wealthy white ghettos.

Shams is proud that the next generation of Bengalis in East London took education very seriously and established themselves in more diverse jobs than their parents, in pharmacy, medicine, banking and IT. Though many of his former clothing worker colleagues still labour long hours, several of them driving minicabs. And he worries about the young people now seeking their fortune in gang-related crime.

Farhana Zaman, a Unite Community trade union and Labour Party activist, settled in Tower Hamlets as a child in the early 1980s. She praises the Bangladeshi community’s contribution to the borough’s cultural life and the growth of Bengali newspapers and TV stations, but would love to see “more inclusion and communities mixing with each other”.

She says that “crimes and tragedies” in Tower Hamlets today are more likely to be “gang-related” than about racism. But racism is still a problem in the area. Zaman highlights racism against EU nationals and Islamophobic attacks that frequently happen on public transport. She believes that the main pressures the community faces are cuts to youth services, and gentrification, which is increasingly pushing Bangladeshis out of Tower Hamlets.

Shahriar Bin Ali, a founder member of the Bangladeshi Workers Council, says, “Young individuals and families can’t afford to live there. The older generation are losing their known neighbourhood and comfort zone and feeling isolated.” He identifies “severe institutional racism in East London”, adding that, “all the recent economic developments have ignored the presence of ethnic communities rooted here.”

He worries that young people have “shifted towards extreme faith beliefs while progressive cultural and political practice has become marginalised.”

To overcome these problems, the Bangladeshi Workers Council wants to revive the assertive grassroots activism and fighting sprit of the 1970s. That spirit will be recalled as people gather in Altab Ali Park at the annual commemoration this week. They will celebrate their achievements and take justifiable pride in having overcome the difficulties they confronted then, while knowing that they are once again facing uncertain times.