“I did not know how much I did not know.”

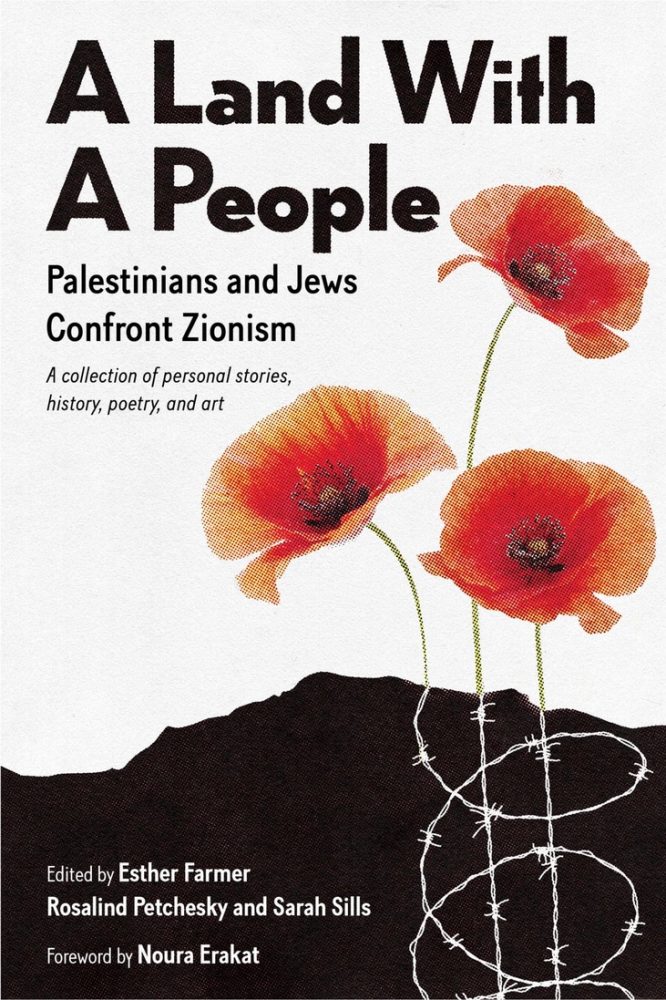

A Land with a People: Palestinians and Jews confront Zionism

A collection of personal stories, history, poetry, and art

Edited by Esther Farmer, Rosalind Petchesky, Sarah Sills

Foreword by Noura Erakat

Monthly Review Press, New York, 2021

Reviewed by Marge Berer*

This collection of stories, history and poetry is a formidable achievement. It is above all about the deep love of its Palestinian authors for the land of Palestine and their identification with it, in the face of the unremitting violence of the Israeli state towards Palestinians, as represented in the politics of Zionism. Like the books of Palestinian human rights lawyer Raja Shehadeh, describing his walks in the hills of Palestine and the changes he saw over many years, this book knocks you over while at the same time being as warm-hearted as it is possible to be. You feel you are walking beside the authors and their families personally, experiencing what made so many of their families emigrate from Palestine while the authors were still children, or even before they were born, in order to survive and find a life and peace elsewhere.

Equally moving, you listen to the Jewish contributors, both US American and Israeli, as they confront the real meaning of Zionism, having to unlearn what was taught to so many of us from the time we were children. To face the fact that Zionism is deeply racist, both in intent and implementation. That Israel actually grants the rights of citizenship only to Jewish people. That their aim has never been to achieve a two-state solution, nor even a one-state solution in which both Jewish and not-Jewish people have full citizenship and equal rights.

Most of the stories and poems in this book are only a few pages, but each one immediately draws you in. Their titles are about displacement, memory, identity, questioning of power, and finally – healing. Only the history section, entitled “Zionism’s Twilight”, is 40+ compelling information-packed pages that will open your eyes as only history can do (pp.15-58).

On the very first page, as you open the cover, human rights attorney and activist Huwaida Arraf says: “This book is an invaluable resource in the effort to challenge the deliberate and dangerous conflation of anti-Zionism with antisemitism, to silence criticism of Israel, and in understanding that the “Israel/Palestine” conflict” is not a religious or ethnic one, it is not even a conflict, but rather an existential struggle… that can and must be undertaken by Palestinians and Jews together”.

On page 65, Riham Barghouti, in a personal memoir called “The necklace”, opens with this paragraph: “I am obsessed with Palestine. I don’t just mean that I love the olive groves, people, land, and the smell of jasmine and cardamom coffee in the morning. I am obsessed with the geography of Palestine. Growing up in New York, I was told over and over again that I didn’t exist, that my people didn’t exist, Palestine didn’t exist. So I searched for Palestine on every map and globe I could find. I knew it was there. I had visited it so many times. One day I happened upon the old globe in the library of Brooklyn Technical High School. I looked at it carefully, sure I was not going to see what I was searching for. However, to my joy and satisfaction, there it was, a small strip of land between Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan, labelled Palestine.”

The biggest myth of all is the claim that Palestine was “a land without a people”, a claim first made by evangelical European Christians and later taken up by the Zionist movement when they were fighting for total ownership of Palestine, also calling it “a land without a people, for a people without a land”, when they knew full well this was untrue. Yet everything followed from that – after World War II, after the Holocaust – as the justification for what Israel has done and become, to make Palestinians leave or become invisible, or be condemned to prison with or without charges, as terrorists, or be killed.

For me, an important moment of awareness, during a play I saw at the National Theatre in London, was when one of the characters says about Israel: “You cannot be both the aggressor and the victim at the same time.”

Gaza, as Rosalind Petchesky reports, which Israel claims they left years ago, is actually the world’s largest open prison. The violence of the Israeli state is a daily event for the Palestinians there, most of them refugees from 1948. “Recurrent bombings of Gaza have destroyed 150,258 buildings and displaced or killed tens of thousands of civilians. Israel also controls all venues in and out of Gaza, restricts the import of food, medical, and building supplies, and restricts electricity access to a few hours a day. As a result of the blockade and attacks, over 90% of Gaza’s water is now undrinkable and according to United Nations’ officials, the conditions of life have become unlivable.” Gaza has nearly 2 million residents, packed into a territory of just over 140 square miles, who can almost never obtain permits to leave.

Yet Mohammed Rafik Mhawesh, a writer who lives in Gaza, says in his essay entitled: “My only weapon is my pencil”: “Walking in my city is special. There are so many faces – some young and looking like they are about to leap into the future with excitement, some looking ancient (probably beyond their actual years) and resigned. So many approaches to religion – some women wearing a full face covering and others with their hair flowing freely. So many “stations” in life – some looking fashionable and others wearing worn-out, second-hand clothes. There are many contradictions: we are not the monolithic “Gaza Palestinian” label the world wants to attach to us. Some people, those who don’t live here, see Gaza City as a hotbed of militancy and terrorism. But those who visit see an ancient culture and an insistence on living and hope.” (p.178)

Tzvia Thier was born in Romania during the second world war. When she was six, her family immigrated to Israel. She grew up in Tel Aviv, spent years on a kibbutz, and was part of a socialist Zionist youth movement. She served in the army. She taught refugees in the Negev, mainly immigrants from North Africa. Then she left and lived in the USA where she taught at a Jewish day school and created curricula for Jewish and Zionist organisations. In 1995 she moved back to live in Jerusalem, where she called herself a liberal Zionist and felt strongly connected to Israel. She thought Israel should withdraw from the Occupied Territories and blamed the settlers for the occupation. She says: “I was against wars, racism, and discrimination, and felt that I had good values. I did not know that I lived behind an invisible wall. I did not know how much I did not know.” She describes how, in school, aged maybe 7 to 18, they had bible studies 3–5 hours a week. The Bible, she says, “was used as a historical document that gave us, the Jewish people, the right to live in the promised land. In other words, a secular society was using a great collection of ancient writings, putting God in the position of a real estate agent.”

The rest of Tzvia’s story, entitled “Seeing Zionism at last”, is about how she came to understand how and why Palestinians are demonised and dehumanised, described as cruel and as backstabbing. Her story shows how sometimes it can take decades before someone understands fully. I recall stories like that from South Africa. The invisible wall between people can be impenetrable unless something specific opens a door. She says in her story she never had any contact with Palestinians, not one neighbour, friend or even acquaintance. I recall some Christians in the USA saying that about Jews and others saying it about black people. Two things changed that, in her case: the war in 1967 and in 2009 the eviction of two Palestinian families from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood of Jerusalem – 32 years later. Her daughter convinced her to participate in the Sheikh Jarrah protest. At the age of 65, she spoke to Palestinians for the first time, having lived in Israel for 59 years. The rest of her story is about how her eyes were opened from that moment on. She ends by saying: “What you finally see, you can no longer unsee.” (p.163)

Perhaps this is a good place to end this review. I’ve taken excerpts from only a handful of the moving stories in this 226-page book, which variously elicit warmth of fellow feeling, tears, laughter and profound anger at different moments. All of the more than 30 other stories, as well as the history, the poetry, the photographs and the resource list at the end, are worth reading. Like Tzvia and like me, you will learn about a lot that you didn’t know. I encourage everyone to read it, especially everyone Jewish. If, like me, you grew up being taught that antisemitism was worse than any other experience of hate, discrimination and violence, and that you were a self-hating Jew if you supported Palestinians’ right to live in their own country, it is a hard road to travel before you recognise that many others have suffered as badly and worse, and that all of us, without exception, are responsible for making sure the violence stops. For me, the fact of the Holocaust is by far the most important reason why Israeli maltreatment of the Palestinian people is unconscionable but also its source, just as men who experience violence from their fathers as little boys often end up being violent in turn towards others – unless they find a way to confront and overcome it. It is the permission to be violent that must be withdrawn, unconditionally.

Marge Berer was the founding editor of the journal Reproductive Health Matters from 1992 to 2015. She is currently the Coordinator of the International Campaign for Women’s Right to Safe Abortion and the Campaign’s weekly newsletter editor. She is also an independent author, editor, lecturer and conference organiser. She has been publishing articles on her blog, The Berer Blog, since 2011 as well as in a wide range of journals, books and magazines. E-mail: marge@margeberer.com

This looks like a book I absolutely have to read. Maybe we should bulk buy!

Hi Naomi, that would make the many wonderful people who wrote and worked on the book very happy! I talked to Daunt Books on Cheapside EC2 this morning. They said they are very happy to order copies of the book from the USA (I think they are US$15 in paperback), either with individuals contacting their closest branch, (listed at https://dauntbooks.co.uk/), or by JVL making a bulk order.

Finding “Palestine” on a old globe and feeling a sense of belonging.

Very moving and so vivid.

I would like to buy this book, if you are going to make a bulk buy order, please let us know how to contribute. Thank you

I would like to be part of a bulk order. let’s see how many of us would like a copy?

Absolutely Naomi.

Many people have observed how similar Russian attacks on Ukranian cities have been to Israel’s assaults on Gaza. It now strikes me that Putin’s refusal to accept that Ukraine is a real state or that there are any such people as Ukrainians is also borrowed from the Israeli playbook on Palestine.

I would sign up to the book order also.

The book is available in Britain from Hive.co.uk, an ethical book supplier. The book is currently in stock there, on sale for £11.49 (RRP £14.99).

You can order it here:

https://www.hive.co.uk/Search/Keyword?keyword=land+with+a+people&productType=0&wgu=10671_9060_16538241710578_d1d8c4fb51&wgexpiry=1661600171

To Rory O’Kellyt. If there was no Israel, I think Putin (Russia’s) actions on Ukraine would be the same,. They are the tactics used by both sides in WW2 for example (including Britain). We don’t need to blame Israel for giving Russia ideas.

Furthermore, it has often struck me how much Israel was formed by Russian ideas and culture. The overwhelming majority of the key ideologues and leaders of the Zionist movement in Palestine and the first 20 years of Israel came directly from what was the Russian empire (ie including Poland, Ukraine, Belarus and so on). I think every PM of Israel in the 20th century either came from there or had one or both parents who did. I’m not sure about Ehud Barak’s parents (he became PM in 1999).