How attacks on “left antisemitism” have ended up defending capitalism

JVL Introduction

Canadian-Jewish academic Moishe Postone (1942-2018) devoted much of his life to reinterpreting Marx’s theory of value and the categories of abstract and concrete labour, use value, (exchange) value and commodity fetishism, as central to critical theory.

So far, so good. But then, in a peculiar development, he applied his insights about value, with its abstraction, invisibility and impersonal domination, to the study of antisemitism.

For him antisemitism becomes a vulgar form of anticapitalism – seeking to personify the elements of capitalism that are so hated. And who better to play this role than “the Jew”.

And where would we find this form of perverted thinking most prevalent? Obviously, on the left with its opposition to capitalism opening the way for seeing it all as the result of the Jews.

Perhaps we’ve been lucky in the English-speaking world that the sheer abstractness and impenetrability of Postone has prevent his theory from getting the grip it has in sections of the German left.

But, as Deborah Maccoby shows in her analysis written especially for this website, of a critique of Postone by Michael Sommer, it is not entirely absent and many prominent critics of what they call “left antisemitism” have been influenced by him.

Sommer’s critique is heavy going – as indeed is Postone – but Maccoby shows its value in inoculating us against the Postone pathogen.

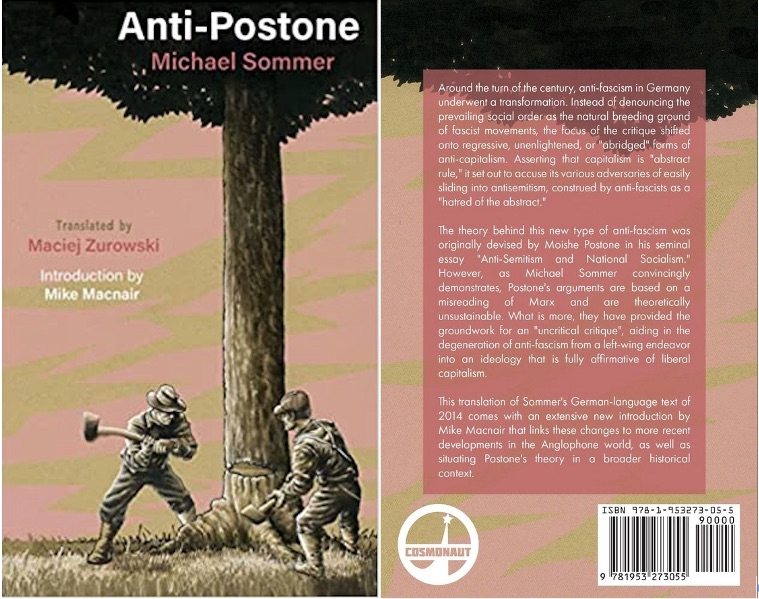

Anti-Postone, or Why Moishe Postone’s Antisemitism Theory is Wrong but Effective, by Michael Sommer

Translated by Maciej Zurowski, Cosmonaut Press, 2021, 73pp.

Anti-Semitism and National Socialism, by Moishe Postone, Chronos Publications, 2000, 27pp.

Reviewed by Deborah Maccoby

Introduction

Few people in the UK have heard of Moishe Postone, but his theory of antisemitism has had a strong influence for decades particularly upon the German left (who are particularly vulnerable to Postone because of guilt over the Holocaust). Mike Macnair (of the Communist Party of Great Britain) writes, in the Introduction to Michael Sommer’s 2014 essay “Wrong but Effective”, that Postone’s 1979 essay “Antisemitism and National Socialism” is “more celebrated” in the US than in the UK, because “the purchase of ‘critical theory’ in the British academic left is….weak”. Brits are not much given to theoretical analysis.

Nonetheless, Postone’s ideas, like a virus, have in recent years percolated into and are spreading in the UK, as theoretical underpinning for the antisemitism smear campaign against Corbyn and his supporters. Even people who have never heard of Postone are unwittingly transmitting his ideas.

Having, in recent weeks, become Postone-aware (I had never heard of him before), I looked up his name in the indexes of three recent books by members of the anti-Corbyn left: a) Antisemitism and the Left (2017), by Robert Fine and Philip Spencer, b) Contemporary Left Antisemitism (2018) by David Hirsh, the founder of the Engage website; and c) Corbynism: A Critical Approach (2018) by Matt Bolton and Frederick Henry Pitts.

All three books tested Postone-positive. The first book has one index reference to Postone and the second has two. The third has five references to Postone in the index – but this seriously underplays the extent of his influence over this book. As Maciej Zurowski comments in his Translator’s Preface, in a footnote about Corbynism: A Critical Approach: “the text was substantially informed by Postone’s antisemitism theory and in fact dedicated to his memory”. This book abounds with references to Corbynism’s “foreshortened” or “truncated” anti-capitalism, or the accusation that Corbynism “remains bewitched by the world of fetishized appearances” (which seems to be the same thing as Postone’s “antinomy” of abstract and concrete (see below).)

I have since look at Daniel Randall’s 2021 book Antisemitism on the Left. Sure enough Moishe Postone occurs seven times in the index and is described, the first time he is mentioned, as “one of the most sophisticated critics of left antisemitism” (p.9).

Adopting the virus analogy, Zurowski writes, in his Preface to “Wrong but Effective”, that his hope is that “Sommer’s vivid exposure of these arguments will contribute towards inoculating the international left against the extreme political degeneration that we have seen in Germany”.

What is Postone’s Theory of Antisemitism?

Postone himself summed up his antisemitism theory in a nutshell:

“The abstract domination of capitalism is personified as the Jews. Antisemitism is a revolt against global capital, misrecognized as the Jews”. (Quoted in Anti-Postone, p. 13)

Sommer’s summary of Postone’s “Antisemitism and National Socialism” essay is slightly longer:

“In but a few pages, Postone’s argument….places ‘modern anti-Semitism’ at the center of the analysis of German fascism, construes it as hatred of the ‘abstract value dimension’ of capitalist society falsely personified in ‘the Jew’ and consequently interprets it as the revolt of a ‘foreshortened anti-capitalism’.” (p.5)

In his essay “Antisemitism and National Socialism”, Postone writes:

“capitalist social relations… present themselves antinomically [i.e. as two sides of the same coin], as the opposition of the abstract and the concrete… This antinomy is recapitulated as the opposition between positive and romantic forms of thought.” (p.15 of Antisemitism and National Socialism, Chronos Publications, 2000).

Postone goes on to say that his essay will focus on the second form of thought:

“forms of romanticism and revolt which, in terms of their own self-understandings, are antibourgeois, but which in fact hypostatize the concrete and thereby remain bound within the antinomy of capitalist social relations.” (Ibid., p. 16)

According to Postone, those who “hypostatize the concrete” believe in a form of anti-capitalism which

“is based on a one-sided attack on the abstract. The abstract and concrete are not seen as constituting an antinomy where the real overcoming of the abstract – of the value dimension – involves the historical overcoming of the antinomy itself as well as each of its terms. Instead, there is the one-sided attack on abstract reason, abstract law, or, at another level, money and finance capital. In this sense it is antinomically complementary to liberal thought, where the domination of the abstract remains unquestioned and the distinction between positive and critical reason is not made…..it is not only the concrete side of the antinomy which can be naturalized and biologized. The manifest abstract dimension was also biologized – as the Jews.” (Ibid., p.21)

To try to sum up: according to Postone, modern antisemites hate capitalism as a form of abstract domination, but they are not able to overcome the capitalist system, because they are trapped in an antinomy between the abstract and the concrete – i.e. a contradiction between two sides of the same coin. They love the concrete and hate the abstract, but they “concretize” or “biologize” the hated abstract, personifying it as the Jews. Postone believes that the only real way to overcome capitalism would entail “the historical overcoming of the antinomy itself as well as each of its terms” — though he never explains in his essay what this “historical overcoming” means.

What are Michael Sommer’s Anti-Postone Arguments?

Sommer writes: “It will become apparent that Postone’s conclusions are based on a questionable method of ‘free association of concepts’” (p.10). Sommer sets out (p.16) to demonstrate that Postone’s understanding of “the abstract value dimension is in fact an amalgam of individual aspects of Marx’s analysis taken out of context, on the one hand, and methodologically conditioned descriptions of this analysis on the other” (i.e. Postone twists Marx’s arguments in order to suit his own agenda).

First, it is essential to read Postone’s essay before tackling Sommer’s critique. Otherwise, Sommer’s exposition, at the beginning of his essay, of extracts from Postone, together with extracts from Marx’s Capital, in order to demonstrate Postone’s misrepresentation of Marx, will appear bewildering — at least to those, like myself, with zero knowledge of Marx’s theory of value. It’s a pity that Postone’s essay couldn’t be included in this booklet – but, of course, copyright laws must have made this impossible. The essay is ubiquitous online (e.g. here) and can also be ordered from Amazon.

Sommer writes: “Our assessment will hopefully make the debate easier to understand and liberate it from the pretense of being some kind of intellectual ‘high bar’ best left to those who possess the relevant skills” (p.16). He offers a “cursory” explanation of Marx’s theory of value in a few pages, for the benefit of the general reader. It is a valiant effort but is hard-going for readers like me. But what does become very clear is the superficial, simplistic and basically meaningless nature of Postone’s theory. Postone’s jargon-ridden style has a strangely seductive, dream-like effect, in that, when reading, one has a sensation of lucidity (this helps to account for his popularity); but when one asks oneself what it means, one doesn’t know. Sommer, in this part of his essay, feels more difficult, because, as an expert in Marx’s theories, he is struggling to convey in simple terms, to the general reader, the real complexity of Marx’s thinking. I don’t think Sommer succeeds in this part of his essay; he seems to me to lack the ability – admittedly very rare — to convey complex ideas in simple terms. But I admire the attempt.

Sommer’s main point is that Postone (claiming to be basing his ideas on those of Marx) conveys a sense of the “abstract value” of capitalism as something over and above human society, whereas to Marx “abstract value” is bound up with and reflected in social relations. Postone’s view of this impersonal domination of abstract values was more fully developed in his 1993 book Time, Labor and Social Domination. Sommers quotes Postone in this book selectively quoting Marx’s Grundrisse, Chapter 3: “individuals are now ruled by abstractions, whereas earlier [i.e. in pre-capitalist, feudal times] they depended on one another”. Sommer points out that Postone omits to say that Marx goes on: “the abstraction or idea, however, is nothing more than the theoretical expression of those material relations which are their [i.e. the individuals’] lord and master.” (pp. 36-7).

Sommer makes the additional points that a) Hitler was not at all anti-capitalist — quite the contrary — and b) modern antisemitism takes many forms other than hatred of “the elegant, civilised Jew Suss who dupes dumb peasants with his arithmetic tricks” (p.50). Sommer mentions the antisemitic images of “the dirty, beast-like ‘eternal Jew’ who transmits diseases and lives in a ‘bug-ridden hole’” or the “’’black-haired Jewish youth‘ – the sex offender who lies in wait for the unsuspicious German girl in order to take her honor’” (pp.50-1). These forms of antisemitism seem to be a projection of subconscious elements within themselves with which antisemites are unable to cope and so displace them upon the Jews.

The Postoneans: Postone’s Followers

The most scathing part of Sommer’s critique is the concluding section on Postone’s followers; and there is a very entertaining Appendix in which Sommers examines various extracts from texts written by these disciples. Sommer comments:

“Because Postone’s text is so vague and tentative, it is actually hard to misrepresent. Just as long as you use the right terms – concrete, abstract, fetish, Jews – it will be alright somehow”.

The most egregious example is the claim that

“this opposition between the abstract and the concrete is materialized today not least in the State of Israel, which is artificial in the best sense of the word, and the blood and soil intifada of the Palestinians, for which the majority of the anti-globalization movement and the peace movement serve as auxiliaries”. (pp.71-2)

Sommers writes that “the abstract/concrete couplet has undergone a peculiar turn: while for Postone it was at least the result of an analysis, however dubious, his disciples use it as an arbitrary guide to tell ‘good’ from ‘bad’” (pp.52-3). Because these “anti-fascist” Postoneans believe that antisemites and fascists “hate the abstract”, they come to think that something that is so much hated by fascists and antisemites must be good – so they end up by loving “the abstract” — ie they support “abstract” capitalism and attack “concrete” anti-capitalists as antisemites and fascists. Sommer points out the irony that Postone himself – in a passage I quoted above, in the section on Postone’s theories of antisemitism, — criticises “abstract”-supporting “liberals”, as the flip side (in Postone’s jargon “antinomically complementary”) of the antisemites who support the “concrete”; he refers to “liberal thought, where the domination of the abstract remains unquestioned and the distinction between positive and critical reason is not made”.

Clearly, Postone did not consciously intend his followers to end up as supporters of capitalism. He believes in the “historical overcoming of the antinomy itself, as well as each of its terms” (whatever this means), as a means of overcoming capitalism. But, as Sommer argues, not only does Postone’s “hatred of the abstract“ theory of antisemitism easily lead his followers to think this must mean “the abstract” is something good; his presentation of “the abstract” as something over and above human society creates a sense of “the abstract” – i.e. capitalism — as a kind of Fate that cannot be changed. Sommer concludes in contrast: “Only human beings can transform and reshape the conditions they have created themselves” (p.58).

Explaining the popularity of Postone’s theory of antisemitism among the German left, Sommer writes:

“Its critique, which has congealed into jargon, suits a left which after 1990 gave up on any possibility of social change. For this left, the ‘Marxist theory of antisemitism’ is highly attractive; it allows you to deem yourself at the forefront of critical consciousness without ever having to talk about the working class or class struggle. On the contrary, you can denounce the ‘common rabble’ as scarred by fetishistic relations. Without ever coming into conflict with the powerful in society, indeed while standing at their side, you can save face as an anti-fascist critic. The professional ideologues of this society have long since understood this.” (p.56)

This is a perfect description of, for instance, David Hirsh and his Engagenik comrades.

Conclusion

Sommer is however, talking mainly about the degeneration of the German Socialist left, rather than about the German equivalent of the right-wing, anti-Corbyn “left” represented by David Hirsh. In his Translator’s Preface, Zurowski writes of the UK Corbyn-supporting left:

“The antisemitism campaign, although originally targeting the left, has paradoxically opened up some of its softer sections to such ideas. It is not inconceivable, then, that Postone’s theses will finally fall on fertile ground in Britain too, offering a superficially Marxist theoretical framework for a left that is temporarily defeated and unwilling to ‘die on that hill’ next time around. In the long run, this could prove a far greater success for the right than the expulsions of left-wingers from the Labour Party were.”

Parts of Sommer’s critique of Postone are difficult to follow, but vaccines often produce side-effects. Anti-Postone seems to me to be a flawed, but nonetheless useful initial inoculation against the Postone pathogen.

You can find a slightly extended version of this review on Amazon under the title Flawed but Useful, .

I wonder if there is any evidence to support these theories of a specific left-wing antisemitism? Are all left-wingers thought to be involved, or half of them, or less?

We know the JPR survey in 2017 showed very low levels of antisemitism (3.6%) rising from the left to right of the political spectrum, so if the theory is correct it can’t involve many left-wingers!

Similarly, according to the CAA Antisemitism Barometer for 2017, 14% of Labour voters agreed that Jewish people tended to chase money (bit like capitalists I suppose), but then again so did 27% Tory voters. Of course only a minority of these voters for either Party would actually dislike Jewish people.

I think I’ll publish a reasonable theory that explains why right-wingers were so anti-Corbyn. Maybe because he threatened their power and privilege, and that an antisemitism smear campaign was a good way to destroy him. They didn’t have any convincing evidence so a couple of theories could always help.

Only racists think Jews are a race. There is no such thing as “the Jews” there is no such thing as “the Jewish Community”. Zionists would like us to believe that there is “a Jewish people” because it is a principal justification for the state of Israel. There can be no “Jewish conspiracy” because for a conspiracy to exist Jews would have to have a uniformity of thought which they quite clearly do not. There are Jewish capitalists and Jewish anti capitalists, Jews from the Middle East, Jews from Africa and Jews from Europe, some Jews believe in God others are atheists. The God some Jews believe in differs quite markedly from faith group to faith group. It’s true that there are some common strands of religious and cultural identity but to suggest that this is a uniformity of purpose is simply nonsense.

Not only is antisemitism a dangerous evil it assumes a uniformity and common purpose that doesn’t exist.

Postone and his theory smacks of desperation.

Some Jews are capitalists but so are some Catholics, Hindus, Protestants and multiple others. So, if we condemn capitalism then we must also be condemning a wide variety of persons. We might also be homophobic as some capitalists must be gay or racist as some will be black.

To condemn capitalism is to condemn what capitalists DO not what they ARE. Do red haired capitalists complain about discrimination??

The whole theory is unadulterated BS and discussing it is a waste of time!

Excellent idea — I look forward to reading your “reasonable theory that explains why right-wingers were so anti-Corbyn” when it is published.

I first came across Postone many years ago while resident in Germany.

His writings managed to influence, indeed become fashionable among, some otherwise good young anti-fascists and managed to disorient them completely.

I must admit that when I tried to read him, I almost lost the will to live.

I think Alan Maddison is on to something.

Didn’t Stephen Pollard claim that Corbyn’s criticism of bankers and the banking system was antisemitic because some bankers happen to be Jewish? And the often bizarrely outspoken Blairite MP Siobhain Mcdonagh, has stated quite categorically that anticapitalism is antisemitism (I wonder if she realises that Labour is supposed to be a democratic socialist party!)

Thank you Deborah for your enlightening review, and thank you JVL for accessing it to me.

Just like Deborah, I had no prior knowledge of Postone’s theory and, in my case, of Sommer’s/Zurowky’s critique thereof.

The notion of “personification of the abstract”, as a social-psychological phenomenon, is perhaps not groundless. Religion would be a prime example. But Marx’s theory of value has little, or nothing to do with it.

This notion could have an analytical value in explaining antisemitism, “old” or “new”, but perception is a matter of exposure. So the question is who propagates it and for what purpose, who stands to gain from it?

We’re all rather constrained in our perception of the present; history enables us us a wider view. Feudal landlords in eastern Europe of old certainly would have benefited from redirecting their subjects’ justified wrath to their Jewish tax collectors. So did Hitler (certainly no “anti-capitalist”) by militating against Jewish bankers, while also portraying Jews as “dirty rats” (this latter description has since shifted to immigrants of other denominations) – since when was prejudice based on logic?

Populism is not a recent phenomenon. Sad as it may be, many people are caught in its web. But in political systems which franchise universal vote, those who fall pray to the “personification of the abstract” vote for Hitler, Trump, Bojo, etc.. , not for Corbyn and his ilk, simply because the latter endanger their respective power structures and, accordingly, have no interest whatsoever in “criminalizing” Jews, Muslims, Gypsies or any other “vertical” section of society, but rather those who occupy the top “horizontal” point thereof. .

I have to say I get quite irritated by this sort of theoretical rhubarb. Why make something that is quite simple seem so complicated?

We all know what constitutes antisemitism and there’s no such thing as left wing or indeed right wing antisemitism – either you’re antisemitic or you aren’t, whatever you believe about anything else!

And there are Labour MPs who welcome this diversion. https://labourlist.org/2019/03/siobhain-mcdonagh-links-anti-capitalism-to-antisemitism-in-labour/

The Siobhain McDonagh interview with BBC radio 4 is mentioned by Zurowski in his Preface. The Preface is on line and is very much worth reading (it’s the clearest part of the booklet):

https://cosmonautmag.com/2022/01/anti-postone-translators-preface/

I don’t believe that anyone would ever have heard of Postone were it not for the fact that his impenetrable ruminations and philosophical obscurantism fulfil an important ideological function aimed quite precisely at naive socialists – namely to justify the conflation of antisemitism with anti-Zionism in order to silence political support for Palestinians. That this was probably not Postone’s subjective intention is of little importance. By comparison the prose of Postone’s epigone David Hirsh displays splendid clarity, which has the great merit of making his false reasoning quite transparent.

However I found JVL’s introduction to the above piece rather strange. It starts with the startlingly ahistorical claim that:

“For [Postone] antisemitism becomes a vulgar form of anticapitalism – seeking to personify the elements of capitalism that are so hated. And who better to play this role than “the Jew”…..”

This is a bizarre formulation because quite obviously Postone did not invent this idea, whose honourable history goes at least back to Marx, not to mention a whole string of 20th century thinkers including Hannah Arendt and Abram Leon.. Why else did Auguste Bebel call antisemitism “the socialism of fools”? Many prominent early “anticapitalist” thinkers who identified as socialist, including Charles Fourier and Proudhon showed marked antipathy to Jews which fits precisely the above description, and this phenomenon continued in the 20th century amongst numerous reactionary political movements claiming to be socialist, and even communist, which exploited socialist and marxist rhetoric.

I personally witnessed such antisemitic rhetoric propagated by the Polish communist régime against its few remaining Jewish citizens in 1968, under the guise of fake “anti-Zionism”. This was a historically earlier conflation of antisemitism with anti-Zionism serving a quite different purpose from the present one.

If you don’t like that idea then, as Richard Feynman famously remarked about quantum mechanics, you’d better find another universe to live in.

People who believe that antisemitism is “discontent … directed against the manifest abstract dimension of capital personified in the form of the Jews” can, simultaneously, believe that antisemitism and anti-Zionism are the same thing. Any theory will do as long as it points to the right conclusion.

Ockham’s razor is a better philosophical guide. We should not accept that anything exists unless its existence has an explanatory function. ‘Left-wing antisemitism’ was postulated to account for processes which are already explained by the ordinary workings of class conflict. Theories like Postone’s are essentially decorative. They add bells and whistles to mechanisms which work fine without them.

For those who like distinguishing ‘abstract’ from ‘concrete’ the point can be expressed differently. Instead of asking the abstract question “Is the Labour Party antisemitic?” we should ask more concretely “What is the Labour Party planning to do because, and only because, it is antisemitic?” To answer this it is not sufficient to trawl through social media accounts. It is necessary to look at documents like the 2017 and 2019 manifestos and see what conclusions can be drawn from the challenges which they put forward to ruling class interests. Are there grounds for claiming that they mean more than they say and, if not, what conclusions follow?

Americans on the far right have claimed that, even without any hidden agenda, socialism and egalitarianism are themselves antisemitic. Some British writers like Siobhain McDonagh and John McTernan are clearly tempted by this. Where does this argument lead?

One cannot imply that socialism is inherently antisemitic without also implying that Jews are inherently capitalistic. The central paradox in this debate is that the whole narrative of Labour Party antisemitism rests on an assumption which is itself not only false but antisemitic.